Mantener y reforzar los logros en Costa Rica

Por Alberto González Pandiella y Alessandro Maravalle, Departamento de Economía de la OCDE

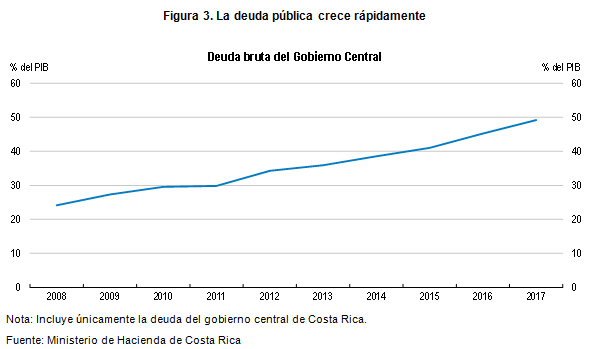

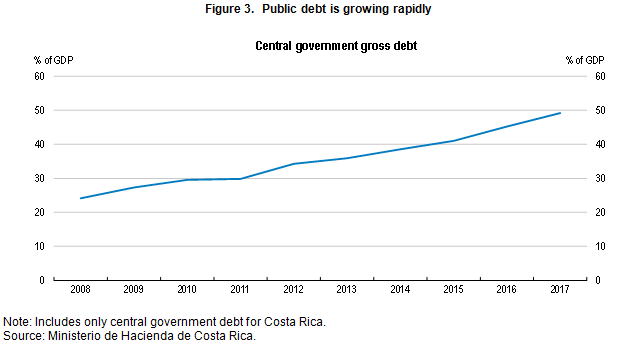

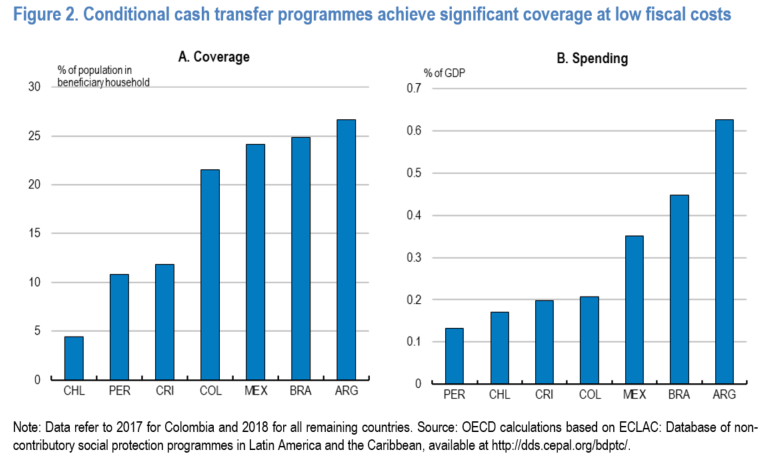

Costa Rica ha hecho un notable progreso económico en las dos últimas décadas, como tener una esperanza de vida equiparable a la media de la OCDE. Gracias a un fuerte compromiso con el comercio, ha logrado atraer inversión extranjera directa y aumentar el nivel de sofisticación de su cesta de exportaciones. Sin embargo, los retos para salvaguardar estos logros y seguir mejorando el nivel de vida son considerables. Las perspectivas de crecimiento se estaban deteriorando antes de la pandemia y, en el futuro, el envejecimiento de la población se cobrará un peaje adicional (gráfico). El desempleo es elevado, con una tasa de dos dígitos desde 2018, así como la informalidad, que afecta a casi la mitad de la población activa. La situación fiscal mejoró en 2021 y 2022, gracias a la reforma fiscal de 2018, pero con una deuda pública en torno al 70% del PIB, las finanzas públicas siguen siendo una vulnerabilidad crítica que requiere esfuerzos sostenidos para contener el gasto e impulsar la eficiencia del sector público. Las tendencias de nearshoring, por las que las empresas buscan reducir los riesgos de interrupción de la cadena de suministro localizándose más cerca de sus mercados finales, están proporcionando nuevas oportunidades de inversión. Costa Rica está a la vanguardia de la protección del medio ambiente y la generación de energías renovables, y la transición mundial hacia la emisión neta cero de gases de efecto invernadero puede aumentar aún más la competitividad del país.

El último Estudio Económico de la OCDE (OCDE, 2023) sostiene que continuar e intensificar los esfuerzos de reforma estructural sería la mejor manera de que Costa Rica respondiera a estos retos y aprovechara las nuevas oportunidades. Las reformas para impulsar la productividad son especialmente críticas para mantener el crecimiento del PIB y del nivel de vida. El fortalecimiento de la competencia es una vía especialmente prometedora para impulsar la productividad. Una competencia débil tiende a traducirse en precios relativamente altos de bienes y servicios para consumidores y empresas. Recientemente se han dado pasos valiosos y audaces para impulsar la competencia en mercados clave, como el del arroz o los servicios profesionales. También se están tomando medidas, en cooperación con el sector privado, para reducir la carga regulatoria, mediante la identificación de reglamentos y procedimientos susceptibles de ser eliminados progresivamente, incluyendo también plazos concretos para su supresión. Dotar a la autoridad nacional de competencia del presupuesto que le otorga la ley es un reto pendiente, que sería especialmente beneficioso en la coyuntura actual, en la que se están tomando medidas para mejorar las regulaciones y abrir sectores clave de la economía. Una autoridad de competencia eficaz, al promover un crecimiento económico más fuerte, también pueden tener un impacto fiscal positivo al apoyar una mayor recaudación de impuestos.

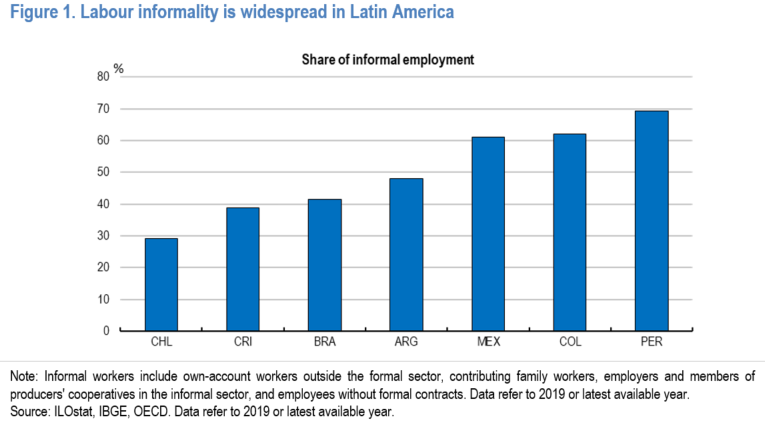

La informalidad, en torno al 45% del empleo total, sigue siendo elevada y es a la vez causa y consecuencia de la baja productividad. Se requiere una estrategia global para reducirla, con acciones necesarias en varias áreas, como reducir los costes laborales no salariales, facilitar la creación de empresas formales, incluso reduciendo el coste burocrático y económico de establecer una empresa formal, ayudar a más costarricenses a adquirir las cualificaciones necesarias para acceder a empleos formales, simplificar los impuestos y mejorar los mecanismos de aplicación. La experiencia de algunos países de la OCDE, como Colombia, indica que la reducción de los costes no salariales, mediante la reducción de las cargas salariales de los empleadores, puede ayudar a reducir la informalidad. Las cargas salariales de los empleadores en Costa Rica son elevadas en comparación con la media de la OCDE, lo que indica que hay un amplio margen para avanzar en esta dirección.

La asistencia sanitaria y la educación primaria prácticamente universales y una de las coberturas de pensiones más altas de la región han dado lugar a resultados sociales notables. Sin embargo, Costa Rica se enfrenta a importantes retos sociales, como el mantenimiento de la pobreza en torno al 20% en los últimos 25 años y el aumento de la desigualdad de ingresos. Hay margen para mejorar la focalización de los programas sociales, ya que en algunos casos más del 40% de los beneficiarios son hogares de ingresos medios y altos. También hay margen para reducir la fragmentación, ya que 21 instituciones se encargan de ejecutar más de 35 programas. Una mejor focalización y una menor fragmentación facilitarían el refuerzo de la protección social en áreas clave y reducirían la desigualdad.

Mejorar la calidad y la eficiencia de la educación y la formación también es clave para apoyar el crecimiento y la equidad en Costa Rica. Aunque el gasto en educación en Costa Rica es elevado, ascendiendo a más del 6,5% del PIB, uno de los porcentajes más altos de los países de la OCDE, los resultados educativos siguen siendo pobres y la exclusión educativa sigue siendo alta, con demasiados costarricenses que abandonan la escuela sin haber cursado la educación secundaria superior. Un apoyo más localizado a los alumnos con dificultades de aprendizaje, la mejora de la selección y la formación de los profesores y la ampliación del acceso a la educación a los niños menores de cuatro años contribuirían a aumentar la igualdad de oportunidades y ayudarían a que más costarricenses accedieran a empleos formales mejor remunerados y a que las empresas cubrieran más fácilmente sus vacantes.

Gráfico. Sin reformas el potencial de crecimiento de la economía caerá al desvanecerse el bono demográfico

Contribuciones al crecimiento potencial, % puntos

Referencias:

OCDE (2023), OCDE Estudios Económicos: Costa Rica 2023, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Por Sonia Araujo y Lisa Meehan, Sección de Costa Rica, Departamento de Economía de la OCDE

Por Sonia Araujo y Lisa Meehan, Sección de Costa Rica, Departamento de Economía de la OCDE