Reaching equal pay: a pending job

By Claudia Ramírez Bulos and Aida Caldera Sánchez, OECD

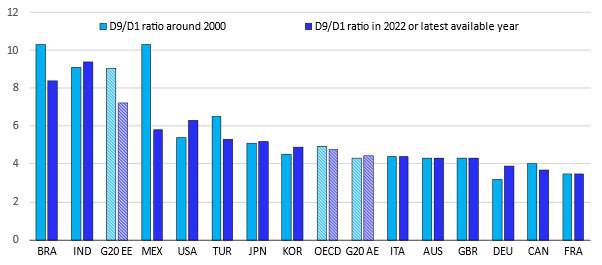

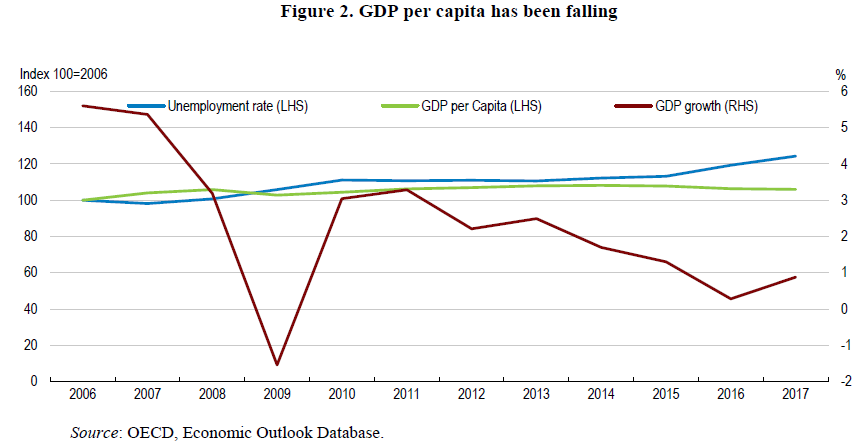

In 2024, a woman working full-time in the average OECD country took home just 89 cents for every dollar earned by a man. But the picture varies significantly by country: in South Korea, women earned 29% less than men, in Japan 22%, while in Italy and Lithuania the difference was closer to 4% (Figure 1). Despite these disparities, one thing is clear: reaching equal pay between men and women is still a pending job across OECD countries.

This picture also emerges clearly in OECD Economic Surveys, which track country-specific progress on gender equality as part of their broader assessment of labour markets and growth. From Germany to Japan, from Korea to Spain, the Surveys show that persistent pay gaps reflect not only individual choices, but structural barriers that limit women’s opportunities to participate fully in the labour market.

Figure 1. The gender wage gap remains large in most OECD countries

Difference in median full-time earnings between men and women, % of the level for men, 2014 and 2024

Note: The data for 2014 refer to 2013 for Chile. The data for 2024 refer to 2023 for Austria, Chile, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, the EU-27, and the OECD. The data for 2024 refer to 2022 for Belgium, Iceland, Israel, Switzerland. For Luxembourg the latest data refer to 2020 (0.4); for Türkiye the latest data refer to 2018 (10.0).

Source: OECD Gender wage gap statistics.

Why equal pay matter

Equal pay isn’t just about fairness, it’s about unlocking economic potential. Paying women fairly for equal work drives higher workforce participation, fuels economic growth, and helps lift families out of poverty. OECD Economic Surveys consistently underline that more equal labour markets are also more productive. Closing today’s gender pay gap builds tomorrow’s gender pension equity, ensuring women enjoy the same financial security in retirement as men.

What is behind the wage gap between men and women?

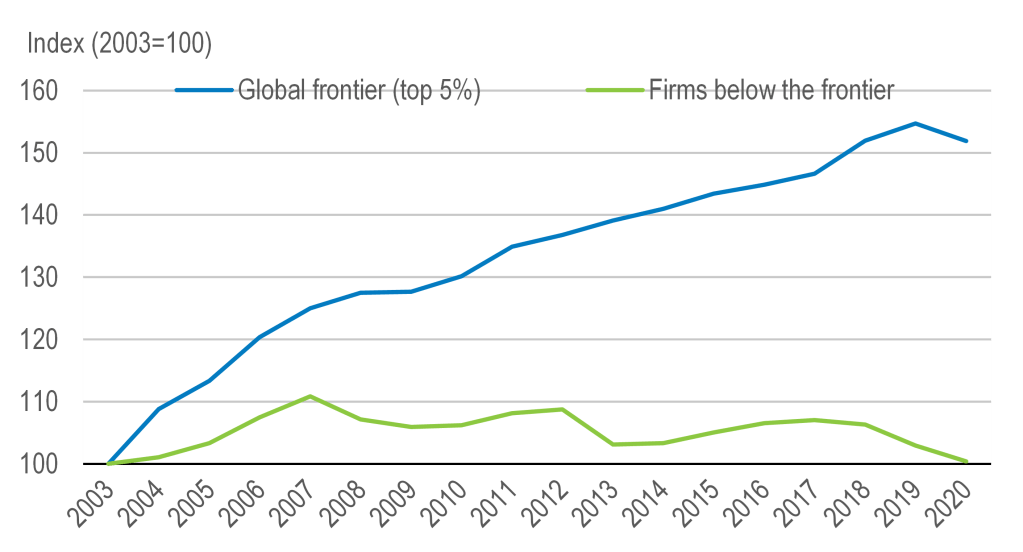

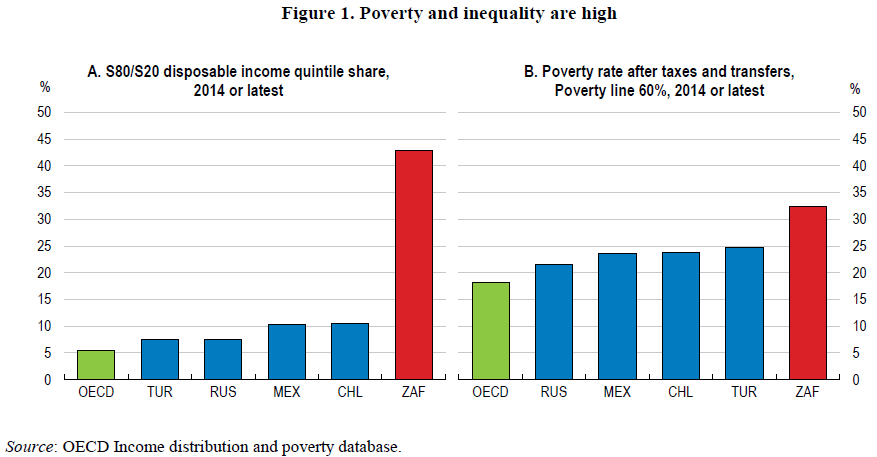

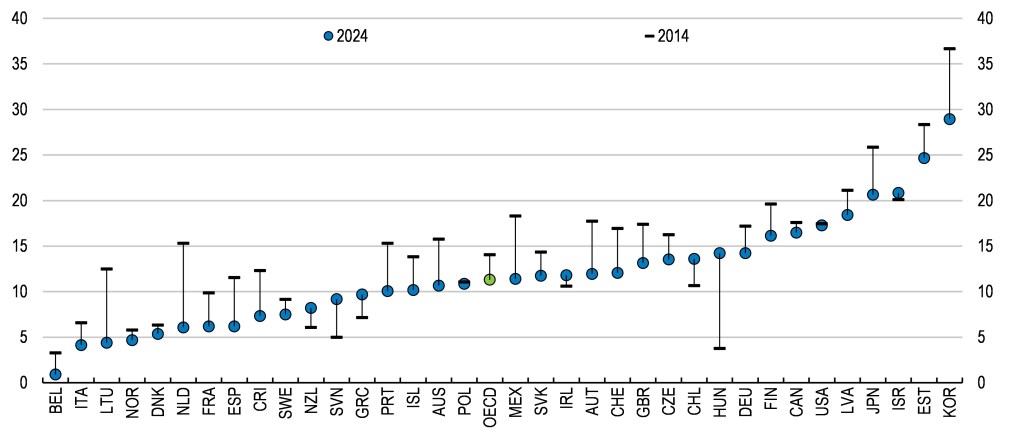

The gender wage gap reflects unequal responsibilities and unequal opportunities. OECD analysis shows that three-quarters of the gap comes from men and women with similar qualifications being paid differently within the same firm, often reflecting differences in tasks and responsibilities, or simply discrimination. The remaining quarter reflects the tendency for women to be clustered in lower-paid firms and industries such as care, health and education, while far fewer make it into high-paying, fast-growing fields like information, communications and technology (Figure 2) (OECD, 2021[1]).

Economic Surveys highlight additional structural barriers:

- In Germany, high marginal tax rates on second earners, often women, discourage full time work (OECD, 2025[2]).

- In Japan, the Surveys stress that limited uptake of parental leave by fathers and unequal career progression for women slows efforts to close the gap (OECD, 2025[3]).

- In Korea, pay transparency and stronger enforcement of anti-discrimination laws are flagged as priorities to tackle one of the largest gender pay gaps in the OECD (OECD, 2024[4]).

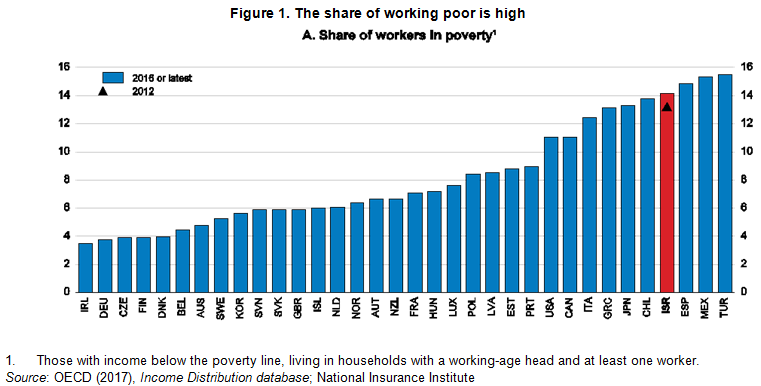

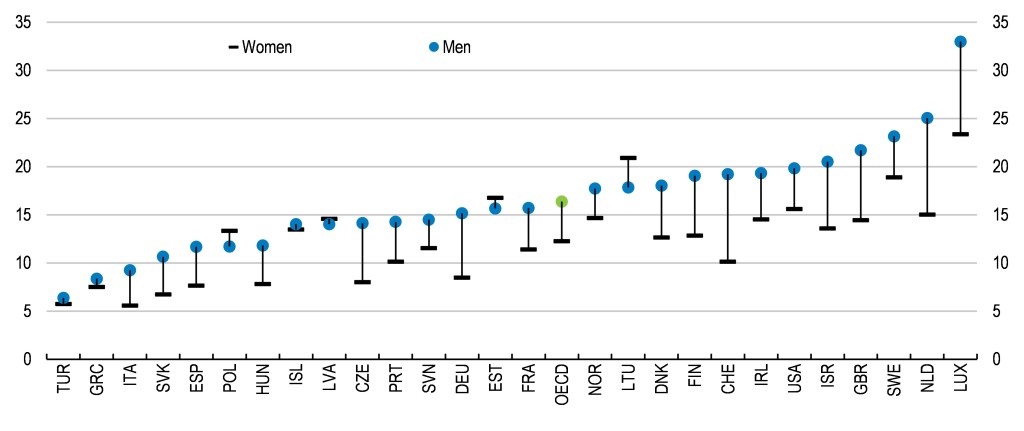

These structural obstacles are compounded by women still bearing a disproportionate share of unpaid household and care work — about four hours a day on average in OECD countries, twice as much as men (Figure 3), leaving less time for paid work, training, or promotions. Also, women’s greater likelihood of working part-time or fewer hours (voluntary and involuntary) limits their experience, career advancement, and access to higher-paying jobs. Hence women not only earn less per hour worked but work less hours on average.

Figure 2. Fewer women work in high-paid jobs than men

ICT specialists and users in their job by gender, % of all jobs, 2022

Source: OECD Going Digital Toolkit gender indicators.

Figure 3. Women assign more time to unpaid household and care work than men

Average time spent by women on unpaid care and domestic work, female to male ratio

Note: “Unpaid care and domestic work” includes routine housework and care for household and non-household members.

Source: OECD Time use database 2024.

Progress and policy lessons

The gender pay gap has narrowed by around three percentage points across the OECD in the last decade (Figure 1), thanks to reforms in education, labour market and social policies. OECD Economic Surveys show how tailored policy packages deliver results.

- Austria reduced its gap through a mix of measures that strengthened pay transparency and reporting laws, reinforced equal treatment and anti-discrimination legislation, and supported women with mentoring programs and initiatives to balance family and work responsibilities — all while encouraging more women to take on leadership roles.

- Spain has also made significant progress, reducing its pay gap by 5.3 points over the past decade. This improvement reflects higher labour market participation, more women moving into full-time roles and higher-paying industries, and the implementation of stronger pay transparency rules to target gender discrimination, which apply to companies with more than 50 employees.

- Australia narrowed its gap through expanded parental leave, subsidised childcare, growth of more flexible work arrangements, wage setting reforms and mandatory pay reporting.

These cases illustrate that progress is possible, but also that achieving pay equity requires a comprehensive approach that tackles barriers at home and in the workplace.

The road ahead

A consistent message across OECD Economic Surveys is that progress requires coordinated action on childcare, family leave, tax design, and workplace practices (Gonne and Trincão, 2024[5]):

- Expanding affordable childcare, improving shared and flexible parental leave.

- Reforming tax and benefit systems to remove disincentives to work for second earners, often women.

- Making fair wage-setting practices including mandatory pay transparency policies, requiring employers to publish gender wage gaps and giving workers the right to know what colleagues in comparable roles earn the norm.

- Supporting women’s access to leadership and decision-making roles such as temporary quotas, mentorship programs, and women’s networks.

- Awareness campaigns and data collection to monitor, evaluate, and improve the effectiveness of policies.

Equal pay will not come automatically. It requires deliberate policy action, sustained monitoring, and a commitment to use all the available talent to strengthen economies and societies.

OECD Economic Surveys will continue to track country-specific progress, helping governments design and implement reforms ensuring that equal pay is not only a principle, but a reality.

References

| Gonne, N. and M. Trincão (2024), “Gender mainstreaming in OECD Economic Surveys”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers No. 1831, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/4d7041d7-en. | [5] |

| OECD (2025), “OECD Economic Surveys: Germany 2025”, https://doi.org/10.1787/39d62aed-en. | [2] |

| OECD (2025), “OECD Economic Surveys: Japan 2024”, https://doi.org/10.1787/41e807f9-en. | [3] |

| OECD (2024), “OECD Economic Surveys: Korea 2024”, https://doi.org/10.1787/c243e16a-en. | [4] |

| OECD (2021), “The Role of Firms in Wage Inequality: Policy Lessons from a Large Scale Cross-Country Study”, https://doi.org/10.1787/7d9b2208-en. | [1] |