How does ageing affect income redistribution?

By Mikkel Hermansen, Economist, OECD Economics Department

In many advanced countries, the share of citiziens having reached post-retirement age is growing fast. Since elderly rely for a good part on a public pension scheme for income support, population ageing tends to result in more income redistribution, in particular in the form cash transfers. However, insofar as ageing also means a growing share of population in groups that are close to retirement age, but still considered as part of the working-age population, a more interesting question is how this facet of ageing affects redistribution. As we show in a recent paper on “Income redistribution through taxes and transfers across OECD countries” ageing actually tends to reduce income redistribution when the latter is measured as the reallocation of resources between people in working-age to limit the influence of redistribution across lifetime. This is primarily a result of ageing being associated with higher employment rates among seniors.

The purpose of redistribution is to reduce income inequality. Therefore it is natural to measure redistribution as the difference between the Gini coefficients of households incomes before and after personal income taxes and cash transfers.[1] This is done only for the working-age population (age 18-65) to avoid the influence of public pensions, mostly reflecting that people pay taxes in working-age they then receive back as benefits in retirement age.

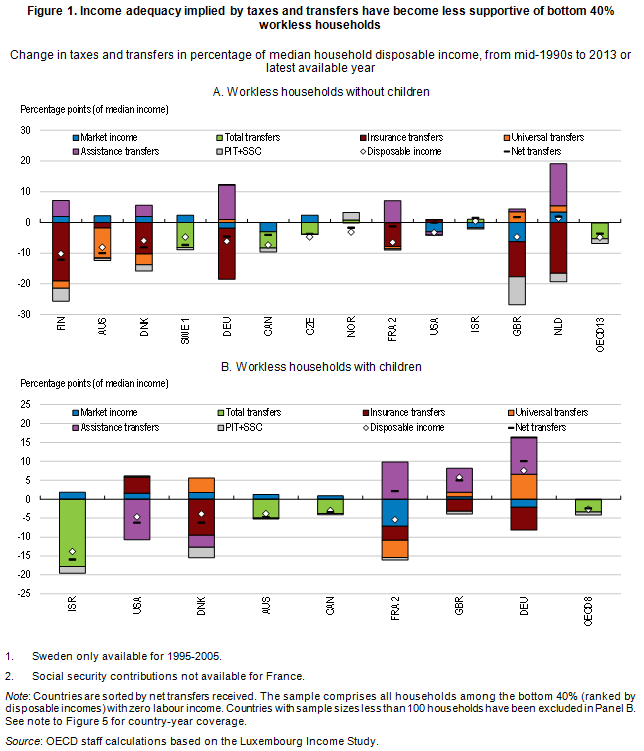

But how does ageing then affect redistribution? As Figure 1 shows, the working-age population has been ageing over the last two decades in the sense that the composition has changed towards relatively more seniors and fewer people below age 40.

Such ageing of the working-age population tends to produce two counteracting effects on redistribution. It may drive redistribution:

- upwards since seniors (age 55-64) approaching retirement are more likely to receive transfers than younger age groups and such transfers are likely to be sizeable, e.g. from early retirement, pension benefits available before age 65 or disability insurance.

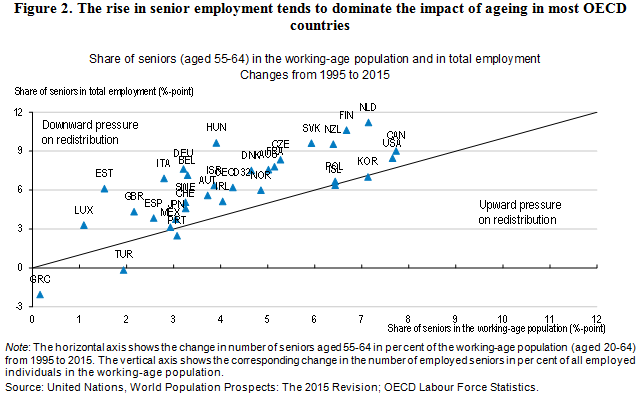

- downwards since more seniors tend to work longer than in the past. Rising life expectancy has generally been associated with more years in good health, which, combined with widespread policy reforms to reduce early withdrawal from the labour market, has implied substantive increases in employment rates among seniors.

A simple empirical exercise shows that the share of seniors in total employment has risen more than the share of seniors in the working-age population in most OECD countries (Figure 2). This suggests that the employment effect has tended to dominate and ageing has thus exerted a downward pressure on redistribution in most OECD countries. We confirm this by computing the change in redistribution with and without the senior group and find for most countries a larger decline in redistribution when including seniors. Nevertheless, for most countries the impact on measured redistribution is limited and is therefore not the main factor driving the overall decline in redistribution observed in most OECD countries since the mid-1990s.

[1] The difference is scaled by the Gini coefficient for households incomes before taxes and transfers to account for cross-country differences in the initial level of market income inequality. See Section 3.4 in Causa and Hermansen (2017) for details.

References

Causa, O. and M. Hermansen (2017), “Income redistribution through taxes and transfers across OECD countries”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1453, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/bc7569c6-en.