Promoting stronger and more sustainable growth for all people across Spain

También disponible en español

By Bertrand Pluyaud and Adolfo Rodríguez-Vargas, OECD Economics Department

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the Spanish economy experienced a period of sustained and more balanced economic growth, less dependent on the construction sector, and with a healthier financial system. The pandemic and Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine were successive shocks that required strong government support to protect businesses and households, as noted in the 2023 Economic Survey of Spain. Output has recovered to its pre-pandemic level, and growth has held up well since the second half of 2022 and it is expected to remain solid in 2024.

The recovery from the pandemic has been steady following the large fall of GDP in 2020

Gross Domestic Product, Volume, base 2019Q4 = 100

Spain has also introduced several major reforms to address longstanding labour market issues, promote business growth and innovation, ensure pensions’ sustainability, and boost vocational education. However, structural weaknesses remain that weigh down Spain’s growth potential. The 2023 Economic Survey discusses policy options to tackle these issues in four areas.

Addressing fiscal challenges

Government action was decisive for the recovery, but it was costly. Public debt, which was already high before the pandemic, has increased by 13 percent points of GDP since 2019. Sustained fiscal consolidation is required to keep debt on a downward path and to make room for ageing-related spending and growth-enhancing items, like education and green transition. This consolidation should rely on both mobilising additional revenues and on enhancing spending efficiency.

Increasing the relatively low tax intake should encompass gradually broadening the value added tax base and raising environment-related taxes, but also reducing tax avoidance and enhancing tax collection. Spending reviews should continue to be used to define growth-enhancing spending priorities, and evaluation of public policies should become the norm.

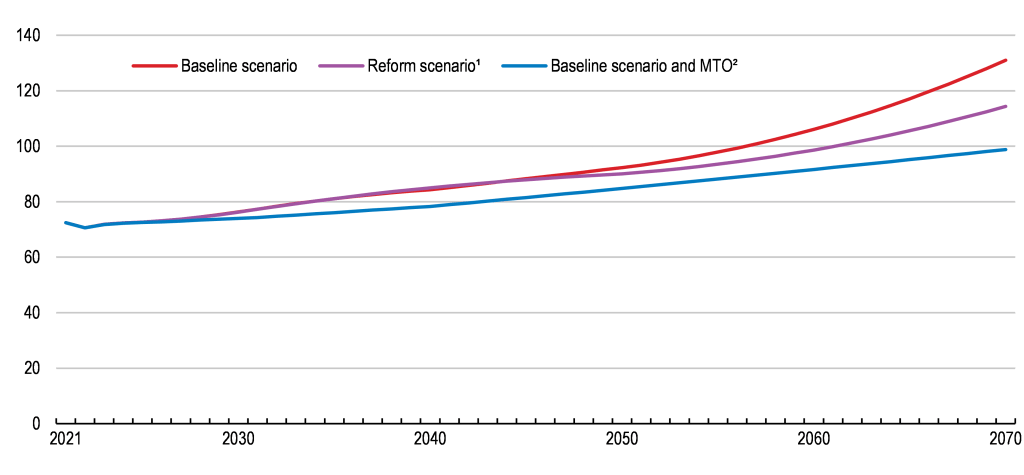

Public debt remains high

Public debt, Maastricht definition, % of GDP

Source: Eurostat.

Raising productivity

Low investment in R&D, inefficient public spending on education and training, and an insufficient stock of ICT capital have dragged down productivity growth, which in the last decade has averaged 0.6% per year compared to 0.9% for the OECD. The share of innovative companies is also comparatively low. All this weighs on potential growth, which with rapid population ageing is expected to weaken even more.

Promoting collaboration and knowledge transfer between businesses and universities, fostering entrepreneurship, reducing regulatory barriers, and improving regulation can increase innovation and business growth. Continuing with an effective implementation of the investment and reforms under the national Recovery, Transformation and Resilience Plan should remain a priority, as it can help overcome structural deficiencies and boost productivity.

Promoting opportunities for all people across Spain

Despite recent improvements, income inequalities remain significant. Poverty is high compared to the OECD, and Spain has the highest child poverty rate in Western Europe, at 22%. This makes it urgent ensuring that public assistance is sufficient and reaches those who need it more. The survey recommends improving the targeting of social benefits, particularly towards poor families with children, boosting the take-up of the minimum income guarantee, and reducing administrative burdens for users.

Young people in Spain face a challenging transition to an independent, productive, and happy adult life. The risk of poverty among them is particularly high, although it has fallen. That is why the special topic of this survey is how can Spain increase opportunities for its young.

Educational and labour market outcomes have improved, but many young people still leave the education system with low education levels or skills, and youth labour-market integration remains difficult. The share of temporary contracts has decreased after the 2021 labour market reform, but it is still high. The survey recommends training teachers to identify and assist students at risk and maintaining support for students to enrol in vocational education, including by fostering the participation of SMEs to offer places. Furthermore, to ease school-to-work transitions it encourages greater employer involvement in the design of university curricula, and improving access to financing for young entrepreneurs.

Housing is a pressing concern for many people in Spain, especially the young. To increase housing supply, the survey recommends expanding the very low stock of social rental housing and relaxing stringent rent controls.

Young people face high poverty risks

Risk of poverty or social exclusion, %

Note: OECD Europe includes European OECD countries and excludes Türkiye.

Source: INE.

Addressing environmental challenges

Spain has made progress in the fight against climate change, as environmental protection expenditure has increased and renewable energies are becoming more prevalent in the energy mix. To keep reducing its dependence on fossil fuels, Spain should accelerate the shift towards greener transportation, improve storage and grid interconnections, and continue promoting renewable energies.

A more environment-friendly tax regime is also needed, as environmental tax revenue as a share of GDP is low compared to most OECD European countries. The base for environment-related taxation can be broadened, including by phasing out exemptions and gradually increasing the tax rate on emissions, while compensating partially and temporarily the most vulnerable.

Persistent drought in some regions has lowered water availability, and intense agriculture production has affected water quality. These problems could be addressed through more efficient irrigation, reuse and recycling of waters, and a more sensible use of fertilizers.

Improving water availability and quality is urgent

Groundwater stations with poor quality standards, %

Note: Groundwater stations failing to meet the drinking water standard under the EU Nitrates Directive

Source: European Environment Agency (EEA).

Government action helped Spain to overcome two major successive shocks. Evidence-based public policies can also help to solve Spain’s longstanding structural weaknesses to increase growth and raise wellbeing for all people across Spain.

References

OECD (2023), OECD Economic Surveys: Spain 2023, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5b50cc51-en