Overcoming persistent obstacles to growth in South Africa

By Nikki Kergozou and Lilas Demmou, OECD.

South Africa, under the Presidency’s Operation Vulindlela, has embarked on bold reforms to address key obstacles to economic growth. Keeping this reform momentum is critical: GDP growth has averaged only 0.7% per year over the past decade. The persistently sluggish pace of GDP growth has failed to significantly raise GDP per capita, expand labour market participation, or improve living standards for the majority of South Africans. The economy’s high emissions intensity presents an additional challenge, as renewed growth may amplify environmental pressures.

In this context, the new 2025 OECD Economic Survey of South Africa (OECD, 2025) contains four main messages:

- The macro-economic policy framework needs to be strengthened to make the economy more resilient.

- Transforming the electricity sector to ensure energy security is vital for economic growth and would, in addition, facilitate the green transition.

- Greater inclusion of South Africans in the labour market is essential for social cohesion and poverty reduction.

- The prospect of higher growth requires speeding up reforms to reduce emissions.

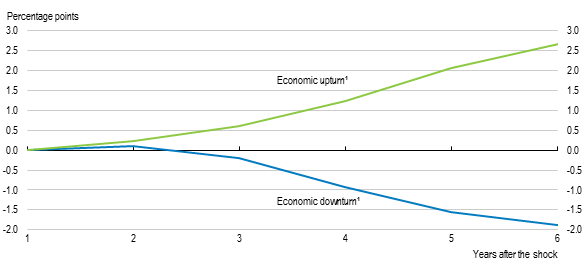

An enhanced macro-economic framework is a prerequisite for stronger sustainable growth. South Africa’s 3-6% inflation target is high and its mid-point is well-above that of other major trading partners. Lowering the inflation target and considering reducing the band around it would help achieve lower inflation and support competitiveness. Public debt has surged from 31.5% of GDP in 2010 to a projected 77% in 2025 (National Treasury, 2025) and rising debt-servicing costs of around 5% are squeezing fiscal space, limiting the government’s capacity to finance social programmes and public investment. Stricter spending controls through reinforced spending rules, and improved governance would help improve the fiscal position and eventually reduce debt. Enhancing the efficiency of tax services, while raising value-added and property taxes, would also contribute to increase revenue collection.

A key structural reform to ensure that growth can be higher in a sustainable way is to ensure that electricity provision is sufficient for businesses to operate. Power outages, or “loadshedding” were estimated to have reduced economic growth by 1.5 percentage points in 2023 (SARB 2024). In addition to directly reducing efficiency, a loss of confidence in the electricity system weakens incentives to invest and deters new market entrants. Significant progress has been made but a lot remains to be done to put electricity outages behind us. Priority should be given to establishing a competitive wholesale electricity market, expanding the transmission grid, and improving municipality’s capacities to deliver electricity effectively. Reforms to municipal management and financing should prioritise earmarking electricity revenues to reduce cross-subsidisation, enhancing property tax collection and exploring distribution concessions.

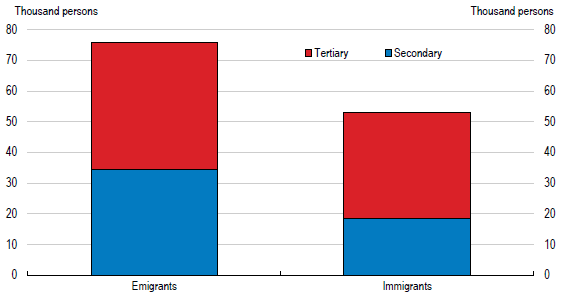

Many South Africans struggle to find work: the country has the lowest employment rate and the highest unemployment rate among G20 economies. Reforms are needed to help firms create more jobs and to also help workers better connect with job opportunities. Restrictive regulations constrain firms’ ability to enter the market and expand, limiting job creation. Urban sprawl and insufficient public transport lead to lengthy, expensive commutes that pose challenges for workers to connect with employment. Promoting densification, and prioritising housing near public transport and development corridors would help.

As reforms leading to higher growth would put upward pressure on greenhouse gas emissions, South Africa will face additional challenges in meeting its climate goals. In addition, the country is highly vulnerable to the changing climate. A greener economy requires higher carbon prices, an enhanced policy framework for faster implementation of policies, and improved public transport so that people use their cars less often. In parallel, adaptation to climate change needs to be accelerated, notably by reducing the severe under resourcing of municipalities, who have a key role to play in climate policies.

References

- OECD (2025), OECD Economic Surveys: South Africa 2025, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/7e6a132a-en.

- SARB (2024), “Monetary Policy Review, October 2024”.

- National Treasury (2025), Budget Review 2025.

Source: Central Statistics Office (CSO)

Source: Central Statistics Office (CSO)