Monetary policy and productivity: Unpacking multifaceted links

By Guido Franco and Filiz Unsal, OECD.

Over the past decades, productivity growth has experienced a significant slowdown across most advanced economies. Existing studies point to a range of structural explanations contributing to this deceleration (André and Gal, 2024), but the recent swift tightening and subsequent easing of the monetary policy stance in many jurisdictions have also renewed interest in understanding whether, and through which mechanisms, monetary policy shifts can influence productivity dynamics.

Our new paper (Franco and Unsal, 2025) provides a comprehensive analysis of the impacts of monetary policy shocks on productivity through both (i) within firm productivity, via modified incentives and capabilities to innovate, adopt new technologies, and invest in capital and labour; and ii) variations in the reallocation of resources across firms with different productivity levels, via the heterogeneous transmission across sectors and firms. The analysis relies on the use of the local projection methodology and a large firm-level dataset, covering both manufacturing and services industries across 24 countries over the 1995-2019 period, matched to a newly published database on monetary policy shocks across countries (Choi, Willems and Yoo, 2024). This setting allows us to overcome the potential endogeneity arising from firms’ expectation of changes in policy rates.

Within firm productivity effects

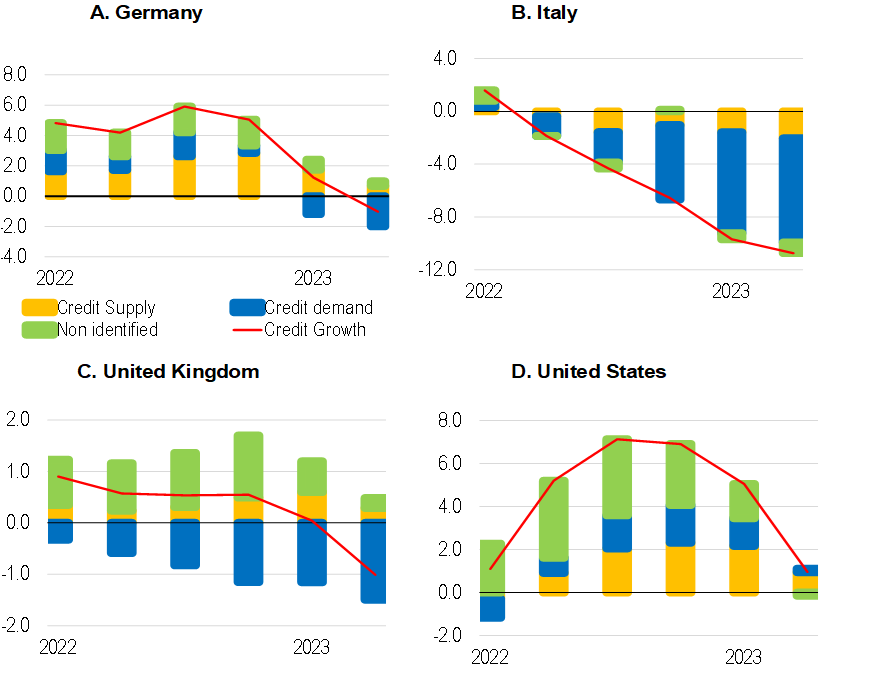

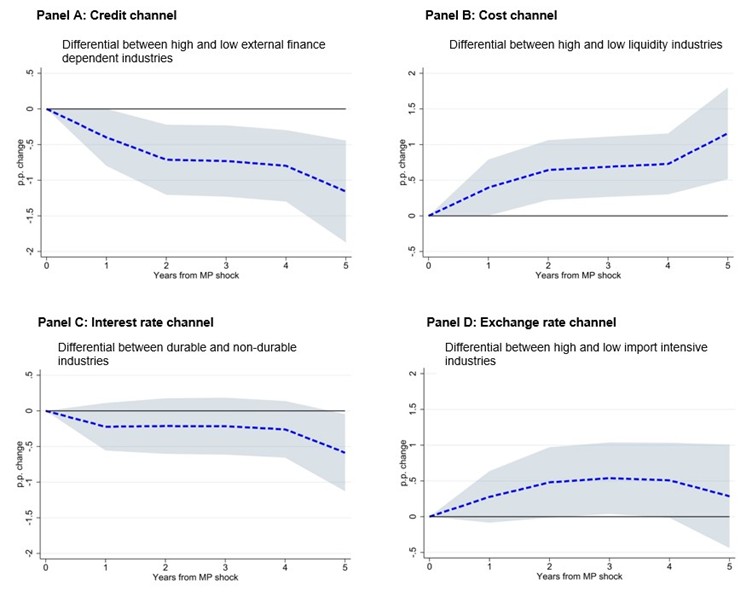

We find that, on average, firm-level productivity growth reacts significantly to changes in the monetary policy stance. A 25 basis points tightening (easing) monetary policy shock implies a cumulative decrease (increase) in productivity growth of 0.7 p.p. over a 5-year time span. Evaluating separately easing and tightening episodes, the former are found to entail slightly larger effects, but the estimates are not far from symmetry. Exploiting the differential effects across sectors and types of firms (Figure 1), we find that the credit and cost channels of the monetary transmission appear to play a relevant role in determining the dynamics of productivity after a monetary policy shock, while the interest-sensitive demand and the exchange rate channels seem to have a more limited and delayed impact.[1]

These effects are amplified or mitigated depending on the country-specific framework conditions and the counter-cyclical response of the policy to the state of the economy. Firms’ productivity is more sensitive to monetary policy shifts in countries with low financial development, in line with the relevance of the credit and cost channels of the monetary transmission. For instance, a developed financial system could allow firms to seek external capital from a variety of sources, attenuating the consequences of a tightening shock. Moreover, firm-level productivity losses (gains) associated with monetary tightening (easing) are only observed when the economy is in a downturn, hinting that a “leaning against the wind” approach to monetary policy appears favourable not only for providing macroeconomic stability but also from a productivity perspective.

Figure 1. The credit and cost channels of monetary policy transmission appear the most relevant in determining productivity dynamics after monetary policy shocks.

Note: In each panel, the graph simulates the impact of a 25 basis points monetary policy shock. The dashed line reports the size of the effect, while the shaded area displays the 90% confidence intervals. Positive (negative) shocks stand for tightening (easing) shocks. Estimates on the interest-sensitive demand channel (Panel C) refer to industrial sectors only.

Source: OECD calculations based on Authors’ calculations based on Orbis, Choi et al. (2024), Demmou and Franco (2021), Durante et al. (2022) and OECD data.

Reallocation effects

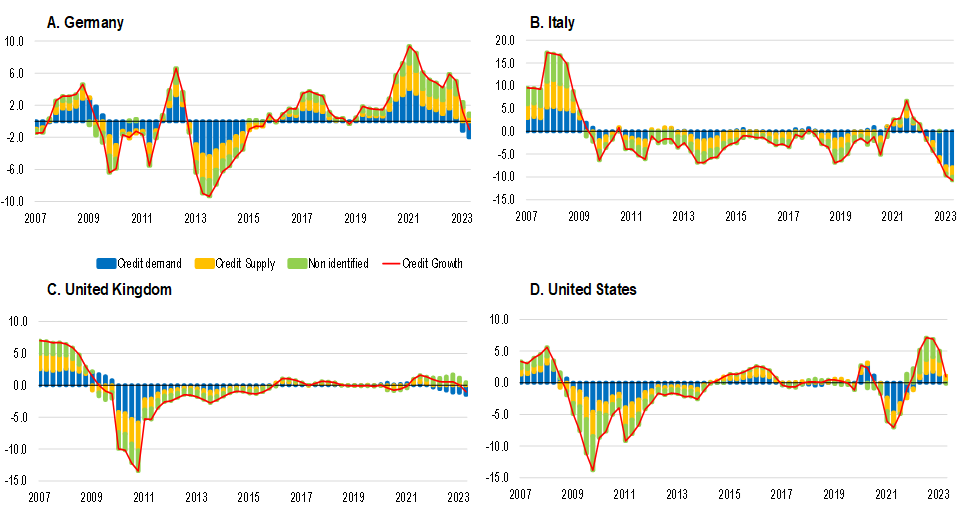

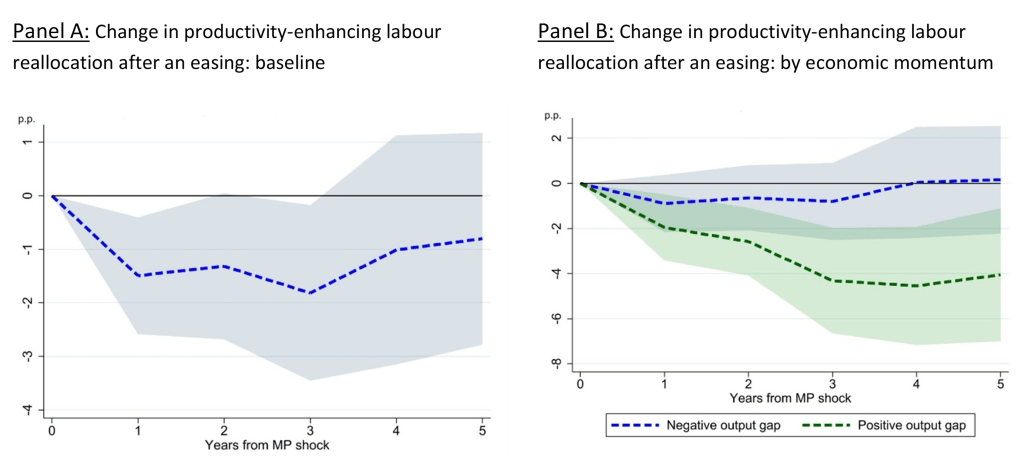

Changes in the monetary policy stance also affect the efficiency with which resources are allocated across firms. Easing episodes are associated with lower productivity-enhancing reallocation, as well as a higher share of labour and capital sunk in zombie firms. The estimated impacts are not extensive but could imply up to a 7% reduction in the efficiency of resources reallocation over 3-years in the aftermath of a monetary easing episode (Figure 2, Panel A).

Critically, the impact is heterogeneous across countries, as it is the case with respect to within-firm productivity effects. Low barriers to competition and a deep and efficient financial system are essential to offset the misallocation effects that may follow a monetary easing episode, for instance by reducing the risk of credit flowing towards zombie firms and ensuring an effective allocation of the credit inflows arising from the relaxation of lending standards. Importantly, a monetary easing reduces the extent of productivity-enhancing reallocation only when it is pro-cyclical: increased misallocation of resources with easing shocks disappears during economic downturns, as the monetary easing may partially compensate for intensified frictions that productive firms may face when the economy is contracting (Figure 2, Panel B).

There is no significant evidence, instead, of the potentially cleansing effects of tightening episodes. Similarly, monetary policy shocks do not alter the productivity-enhancing nature of business dynamism through the extensive margin, as our estimates show that the strength of the (inverse) relationship between firm exit and productivity is unaffected. Still, when turning to business dynamism more broadly and using sector-level data, we find that the entry and exit margins adjust in opposite directions: a tightening (easing) implies higher (lower) bankruptcies and lower (higher) 1-year survival rate of newly born enterprises.

Figure 2. Monetary easing reduces the productivity-enhancing reallocation of labour, prevalently when it is pro-cyclical.

Note: Productivity-enhancing labour reallocation is measured as the strength of the relationship between firms lagged productivity and employment growth, and hence as the differential employment growth of higher productivity firms compared to lower productivity ones. The graphs simulate the impact of a 25 basis points monetary policy easing surprise.

Source: OECD calculations based on Orbis, Choi et al. (2024) and OECD data.

Conclusion

Productivity dynamics are significantly influenced by monetary policy shocks, but the impacts may depend on the transmission channels involved, country-specific framework conditions and cyclical alignment of the monetary policy responses.

Specifically, a monetary easing boosts firm-level productivity in the medium-term, mainly through investment, but also tends to slow down the productivity-enhancing nature of labour and capital reallocation across firms. On the other hand, tightening episodes are detrimental for firm-level productivity and neutral from a misallocation perspective. The productivity benefits are larger and the losses smaller when sound policies are implemented. Developing a deep and stable financial system, ensuring competitive product markets, while avoiding pro-cyclical changes in the monetary policy stance, helps leverage the advantages and minimise the productivity damages associated with policy rates shifts.

References

André, C. and P. Gal (2024), “Reviving productivity growth: A review of policies”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers No. 1822, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/61244acd-en.

Choi, S., T. Willems and S. Y. Yoo (2024), “Revisiting the monetary transmission mechanism through an industry-level differential approach”, Journal of Monetary Economics, Vol. 145, 103556, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmoneco.2024.103556.

Demmou, L. and G. Franco (2021), “Mind the financing gap: Enhancing the contribution of intangible assets to productivity”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers No. 1681, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/7aefd0d9-en.

Durante, E., A. Ferrando and P. Vermeulen (2022), “Monetary policy, investment and firm heterogeneity”, European Economic Review, Vol. 148, 104251, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2022.104251.

Franco, G. and F. Unsal (2025), “Monetary policy and productivity: Unpacking multifaceted links”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers No. 1843, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/e1d617b2-en.

[1] The credit channel relates to the sensitivity of the external financing premium to changes in policy rates. The interest rate channel is the driven by the impact of changes in interest rates on the interest-sensitive component of demand. The exchange rate channel concerns the negative impact that a tightening (easing) could have on exporting (importing) industries through the appreciation (depreciation) of the domestic currency. The cost channel is instead related to firms’ need to pay factors of production before receiving sale revenues, and thus to borrow some working capital; a change in the cost of borrowing would then be alike to a change in inputs prices.