Informality and weak competition – a deadly cocktail for growth and equity in emerging Latin America

By Piritta Sorsa, Jens Arnold and Paula Garda, OECD Economics Department

Why is growth persistently low and so unevenly distributed in emerging Latin America compared to emerging Asia despite a huge potential? Potential growth is ranging around 2-3% in the region. Some refer to dependence on commodities, poor education, weak business environments or corruption as possible causes. But the question is deeper and more complex. A crucial factor for Latin America is low productivity, often related to a poor use of available resources. Across the region, many workers and significant amounts of capital are stuck in activities that are not efficient. The reasons for this are many, but two important forces stand out: high informality and weak competition.

High and persistent informality in the region leaves workers more vulnerable and deprives them from social protection, thus contributing to inequality. For example, old age poverty in Colombia is high as low-skilled workers spend much of their working lives in informal employment, without pension contributions (OECD, 2019[1]). In Brazil and Argentina, informal workers retire later than others for the same reason, until they eventually reach the age to benefit from a non-contributory pension (OECD, 2019[2]; OECD, 2018[3]). In Mexico, poverty and informality are highly correlated among regions (OECD, 2019[4]). Informality also tends to maintain companies small with often low productivity as growing would face high costs of formalisation. Indeed, informal-sector productivity in the average LAC country is only between 25 and 75 percent of total labour productivity, and productivity decreases as informality rises (Loayza, 2018[5]). Informality also reduces the tax base for corporate and personal income taxes, reducing the capacity of the public sector to boost productivity and reduce inequality, and requires a higher tax burden on larger formal companies.

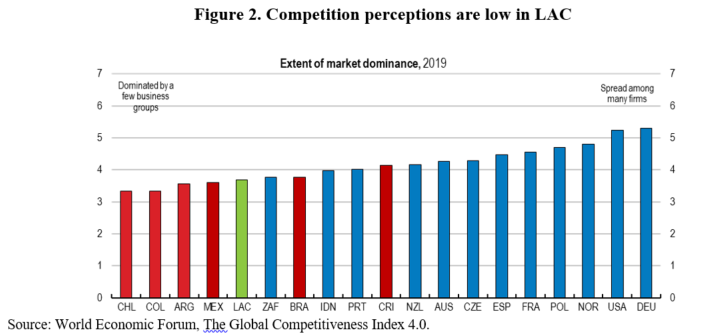

Weak competition is a second reason behind low productivity and is often reflected in high concentration (Figure 2). Entry barriers can protect existing activities that have little future growth potential at the cost of new dynamic and productive firms. Weak competition creates rents and lowers the share of wages in value-added worsening income distribution. Higher prices for consumers reduce purchasing power, affecting disproportionally low-income households.

Reducing informality for productivity and equity

The causes of informality are multiple. Informality is often a consequence of high costs of hiring formal workers, both wage and non-wage, especially in relation to labour productivity, given low educational outcomes.

Where high informality and weak competition coincide, as is the case in many Latin American countries, the consequences for both growth and equity can be particularly severe. For emerging Latin America to grow stronger and better share the fruits of growth, dealing with informality and competition should be priority.

Labour informality is often caused by rigid labour regulation. High firing costs of workers can discourage formal-sector hiring and promote inequality (Loayza, 2018[5]; OECD, 2018[6]; Heckman and Pages, 2000[7]). In Mexico, a labour reform in 2012 reduced hiring and firing costs, introduced different models of contracting and brought changes to the resolution of labour conflicts. Formal salaried jobs increased in the aftermath (OECD, 2019[4]). Minimum wages can be high compared to productivity or average wages keeping most workers informal. In Colombia, the minimum wage is close to the median wage and two thirds of workers earn less than that (OECD, 2019[1]). High payroll taxes can also have a detrimental effect on informality rates (Bobba, Flabbi and Levy, 2018[8]). Antón and Rastaletti (2018[9]) show how lowering employer social security contributions could lead to a substantial increase of labour formalisation. At a minimum, lower employer contributions could be offered temporarily for hiring low-skilled workers that enter the formal sector for the first time (OECD, 2017[10]). Lowering payroll taxes in Colombia helped reduce informality after the 2012 reform (Kugler et al., 2017[11]; Morales and Medina, 2016[12]; Fernández and Villar, 2016[13]; Bernal et al., 2017[14]). While incentives are crucial, better enforcement also needs to be part of any formalisation strategy.

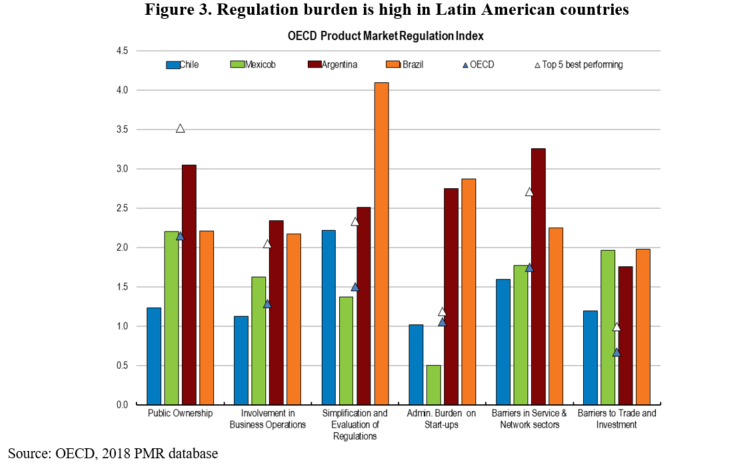

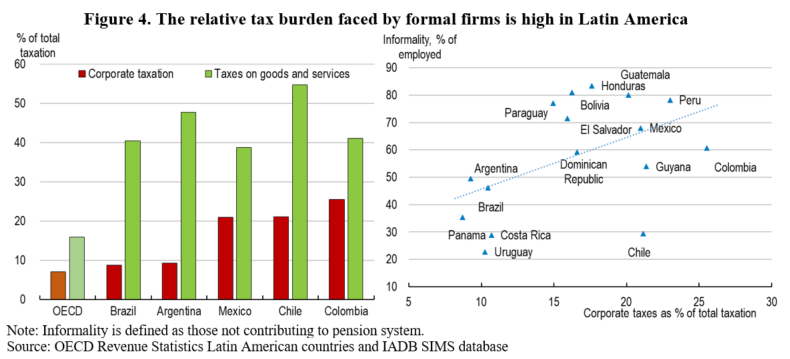

Cumbersome administrative barriers and high taxes can keep companies informal. Latin America stands out in this respect (Figure 3). The tax burden on formal companies is also high compared to the OECD and positively associated to informality rates (Figure 4). To promote formalisation, regulatory and tax systems should be simple, with gradual increases in the tax burden as firms grow, so as not to discourage growth, and keep marginal tax rates as low as possible (Loayza, 2018[5]). These characteristics are crucial to encourage investment and employment in growing and larger companies.

Many countries in the region have implemented simplified schemes and reduced costs for small taxpayers with the aim of reducing informality. For example, Mexico introduced a special simplified regime for SMEs (Regimén de Incoporación Fiscal, RIF) in 2014, which induced 1.5 million informal firms to join the tax system (OECD, 2018[15]). In Brazil, a special tax regime for microenterprises (Microemprendedor Invididual, MEI) reduced the cost of formalisation and contributions to social security as of 2008. This regime helps explain the rising formalisation of the self-employed, including of women (OECD, 2012[16]). In Argentina, a simplified tax regime called Monotributo helped formalise self-employed workers. In Colombia, the tax reform in 2018 introduced a new simplified tax scheme (Simple) for small firms, and there are signs of positive impact on firm formalisation during 2019. At the same time, these regimes have to be designed carefully. When participation thresholds for special SME tax regimes are set too high, the effectiveness for formalisation declines while fiscal cost and threshold effects rise, as in the case of Brazil’s Simples Nacional (OECD, 2018[3]). At times, simplifying the general tax regime may be preferable over creating exceptions.

Education and skill levels are also linked with informality. Countries with lowest informality rates tend to have significantly higher levels of human capital (Docquier, Müller and Naval, 2017[17]). It is not a coincidence that the decrease in informality over recent decades in Latin America went hand in hand with steady progress towards universal education. Evidence shows that improvements in education have been an important driving force behind falling informality in Colombia and Brazil (International Monetary Fund, 2018[18]; OECD, 2018[3]).

Increasing competition for productivity and equity

In Latin America, the same complex rules that discourage formal job creation often coincide with overly strict regulations that stifle competition. Competition is affected by how easily firms can enter or exit markets, by the extent of license requirements for starting or expanding a business and by competitive pressures from imports. Relatively high trade protection adds to this in a number Latin American countries, shielding domestic producers from international competition (OECD, 2018[3]). All of this tends to raise prices for consumers and keep resources in low-productivity activities where informality is widespread, for both workers and firms.

These circular relationships suggest that it is important for the public sector to take stock of burdens that even well-intended regulations and codes can impose on private activity. Disincentives for firms to go formal will inevitably preclude workers from the benefits of formal jobs, while unnecessary barriers to competition will keep more jobs in activities with limited potential for productivity and wage growth. To foster formal job creation, all parts of a country’s regulatory framework should be simple and clear, promote competition, and facilitate both market entry and exit of firms (Loayza, Oviedo and Serven, 2005[19]).

Getting there

A comprehensive strategy is needed to deal with both informality and competition. It involves simplifying labour regulations, keeping administrative burdens and license requirements for companies as easy as possible, facilitating market entry and reducing trade barriers. Bringing more workers and firms into the formal sector would bring about broader social and labour protection, fairer wages, a more even tax burden and higher potential growth. Many of these policies are politically difficult as they involve dealing with vested interests and require appropriate sequencing. But that is not an excuse for inaction. These reforms should be accompanied with training and other active labour market policies for affected workers, as the informal sector often fulfils the function of absorbing excess labour supply, especially during transitions or economic recessions. Reforms to improve quality and relevance of education to raise worker productivity and policies that can raise investment and boost firm productivity should be also part of the strategy.

References

Antón, A. and A. Rasteletti (2018), Imposición al trabajo en contextos de alta informalidad laboral: Un marco teórico para la simulación de reformas tributarias y de seguridad social, Inter-American Development Bank, Washington, D.C., http://dx.doi.org/10.18235/0001467.

Bernal, R. et al. (2017), “Switching from Payroll Taxes to Corporate Income Taxes: Firms’ Employment and Wages after the Colombian 2012 Tax Reform”, IDB Technical Note, No. 1268, Inter-American Development Bank.

Bobba, M., L. Flabbi and S. Levy (2018), “Labor Market Search, Informality and Schooling Investments”, Interamerican Development Bank, https://publications.iadb.org/en/publication/12928/labor-market-search-informality-and-schooling-investments.

Docquier, F., T. Müller and J. Naval (2017), “Informality and Long-Run Growth”, The Scandinavian Journal of Economics, Vol. 119/4, pp. 1040-1085, http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/sjoe.12185.

Fernández, C. and L. Villar (2016), “The Impact of Lowering the Payroll Tax on Informality in Colombia”, No. 72, Fedesarrollo, http://hdl.handle.net/11445/3300.

Heckman, J. and C. Pages (2000), “The Cost of Job Security Regulation: Evidence from Latin American Labor Markets”, NBER working paper, No. 7773, National Bureau of Economic Research, http://dx.doi.org/10.3386/w7773.

International Monetary Fund (2018), “Colombia: Selected Issues”, Country Report, No. 18/129, http://www.imf.org.

Kugler, A. et al. (2017), “Do Payroll Tax Breaks Stimulate Formality? Evidence from Colombia’s Reform”, NBER Working Paper Series, http://www.nber.org/papers/w23308.

Loayza, N. (2018), “Informality : Why Is It So Widespread and How Can It Be Reduced?”, Research and Policy Briefs, No. 20, World Bank, http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/130391545228882358/Informality-Why-Is-It-So-Widespread-and-How-Can-It-Be-Reduced.

Loayza, N., A. Oviedo and L. Serven (2005), “The impact of regulation on growth and informality – cross-country evidence”, Policy, Research working paper World Bank 3623, http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/212041468134383114/The-impact-of-regulation-on-growth-and-informality-cross-country-evidence.

Morales, L. and C. Medina (2016), “Assessing the Effect of Payroll Taxes on Formal Employment: The Case of the 2012 Tax Reform in Colombia”, Borradores de Economia, Banco de la Republica, http://www.banrep.gov.co/en/borrador-971.

OECD (2019), Economic Surveys: Colombia, https://doi.org/10.1787/e4c64889-en.

OECD (2019), Economic Surveys: Mexico, https://doi.org/10.1787/a536d00e-en.

OECD (2019), OECD Economic Surveys: Argentina 2019, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/0c7f002c-en.

OECD (2018), Economic Surveys: Chile, https://doi.org/10.1787/eco_surveys-chl-2018-en.

OECD (2018), Getting it Right: Strategic Priorities for Mexico, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264292062-en.

OECD (2018), OECD Economic Surveys: Brazil 2018, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eco_surveys-bra-2018-en.

OECD (2017), OECD Economic Surveys: Argentina 2017: Multi-dimensional Economic Survey, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eco_surveys-arg-2017-en.

OECD (2012), Closing the Gender Gap ACT NOW: Brazil Country note, OECD, Paris, France, http://www.oecd.org/gender/closingthegap.htm.