Statistical Insights: The ADIMA database on Multinational Enterprises

by Graham Pilgrim, OECD Statistics and Data Directorate

Multinational Enterprises (MNEs) have been at the forefront of changes in the global economy over the last few decades, as trade and investment barriers have been removed and transportation and communication costs have declined. In a world of global value chains, understanding MNEs – where they are, how they operate, and where they pay taxes – has never been more important. However, surprisingly few official statistics are currently available on individual MNEs.

To fill this gap the OECD has begun to develop a new database – the Analytical Database on Individual Multinationals and Affiliates (ADIMA) – using a number of open “big data” sources that can provide new insights on individual MNEs and their global profiles.

What is ADIMA?

ADIMA has four components:

Physical Register: Offering a comprehensive view of each MNE and its subsidiaries.

Digital Register: Showing all websites belonging to each MNE.

Indicators: Providing harmonised data at the global level for each MNE.

Monitor: Identifying events like large company restructurings that can give early warnings of potential significant impacts on trade, GDP and FDI data.

This information already covers 100 of the world’s largest MNEs, and more will be added in future releases.

What does ADIMA tell us on taxes?

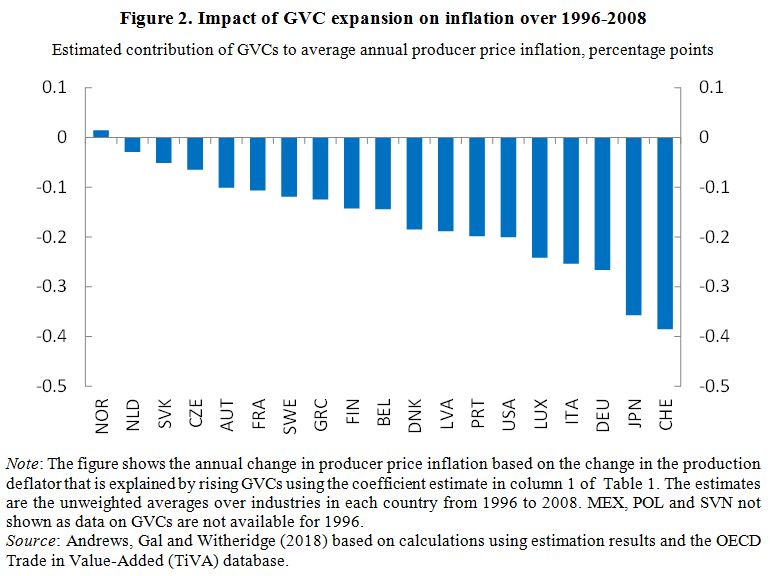

At an aggregate level, ADIMA shows that in 2016 the 100 MNEs covered in the the database (ADIMA-100) generated nearly $10 trillion in revenues (almost 20% of global GDP), earned $730 billion in profits and paid $185 billion in taxes. But you can also drill down and get more targeted information. For example, although the average Effective Tax Rate (ETR) of the ADIMA-100 was about 25%, it was significantly lower for MNEs producing computers and electronics, and pharmaceuticals, who have substantial intangible assets that they can locate in lower-tax economies (Figure 1).

Where are firms physically located?

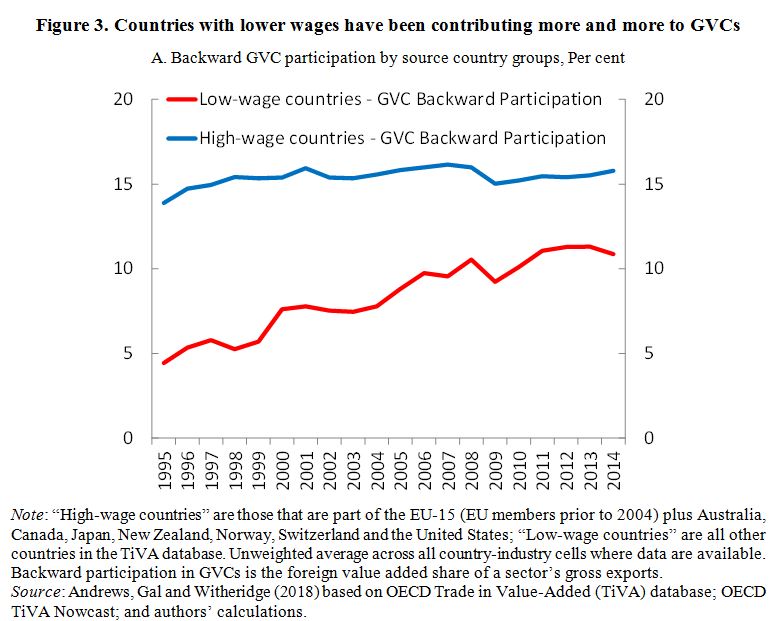

The physical register provided by ADIMA describes how MNEs structure their physical operations across countries. Here ADIMA’s innovative tools and variety of data sources go beyond the information typically available in company reports (Figure 2), enabling deeper analysis and a mechanism to help profile firms and their affiliates in national and international statistical business registers. For example, companies’ annual reports show that 74 of the ADIMA-100 have a physical presence in the United Kingdom, with an additional 11 MNEs identified using complementary sources (e.g. Legal Entity Identifier, Website Hyperlink Graphs, Server Security Certificates and WikiData), bringing the number of ADIMA-100 MNEs operating in the United Kingdom up to 85.

What about MNEs’ digital presence?

Physical presence may not reflect digital presence, that is, and in particular for firms whose only penetration into markets is through country-specific websites (i.e. no physical presence). This matters, especially for statistics on highly digitalised MNEs, as the provision of digitised services blurs the traditional line between companies with a foreign presence and those that trade across borders which may affect the comparability of international data on trade and national income.

Digital channels are comparable in scale to physical channels: the ADIMA Digital Register captures 20,000 websites while the ADIMA Physical Register captures 26,000 subsidiaries. In smaller countries the digital presence is often more important: for example, only 10 of the ADIMA-100 are physically present in Estonia but a further 19 mainly “digitalised” companies have an electronic presence (Figure 2).

Looking at another interesting example, annual Reports for Alphabet, Google’s parent company, show subsidiaries in two OECD countries but ADIMA’s physical and digital registers record subsidiaries and/or national websites in all OECD countries. For any given domain name, advertising revenue may be recorded as either a domestic or a cross-border transaction. The choice may depend on whether the country-specific site has been legally registered in that country.

Next Steps

The OECD plans to collaborate with interested official statistical agencies to improve both national statistics on MNEs and ADIMA data. The collaborations should also consolidate the tools developed in ADIMA, extend its coverage of MNEs, improve its methods and incorporate new data sources.

The measure explained

The OECD Analytical Database on Individual Multinationals and Affiliates (ADIMA) is a new data framework offering information on both the physical and digital presence of MNEs by country. It combines information from traditional sources such as companies’ Annual Reports with newly emerging sources such as the Legal Entity Identifier, Website Hyperlink Graphs, WikiData, OpenStreetMap and Server Security Certificates.

Where to find the underlying data?

Further reading