Brexit and Dutch Exports: Fewer glasshouses, more glass towers as agri-food shrinks and finance gains.

by Donal Smith, OECD Trade Directorate and Economics Department

The Netherlands is likely to be one of the European countries that is going to be significantly affected by the United Kingdom’s planned departure from the European Union (Brexit). As an open economy with strong trade and investment links to the United Kingdom, the Netherlands is exposed to increases in barriers to trade between the United Kingdom and EU (Vandenbussche et al., 2017). New OECD simulations show the potential extent of this impact, as well as the different sectors of the Dutch economy likely to be affected.

The Netherlands is likely to be one of the European countries that is going to be significantly affected by the United Kingdom’s planned departure from the European Union (Brexit). As an open economy with strong trade and investment links to the United Kingdom, the Netherlands is exposed to increases in barriers to trade between the United Kingdom and EU (Vandenbussche et al., 2017). New OECD simulations show the potential extent of this impact, as well as the different sectors of the Dutch economy likely to be affected.

The sector-level impacts will depend on differing UK trade exposures, tariff rates and non-tariff measures (NTMs) applied to different products; varying degrees of global value chain integration of the sectors; and differences in sectors trade diversification opportunities. On trade exposure for example, the agri-food sector has a comparatively high UK exposure. This sector accounts for 23% of the total exports of the Netherlands to the UK while the UK market makes up 12% of total Dutch agri-food exports (OECD 2018).[1]

An illustrative worst-case Brexit scenario – assuming the UK leaves the EU without any trade agreement – is simulated using the OECD METRO model (OECD, 2015).[2] The key advantage of this analysis is that it accounts for changes in both tariff and non-tariff barriers. The scenario assumes that trade relations between the EU and UK default to the World Trade Organisation’s (WTO) Most-Favoured Nation (MFN) rules, that is, the most basic trade relationship. Relative to current arrangements, this corresponds to an increase in tariffs on Dutch trade with the United Kingdom of between 0 and 12 per cent.

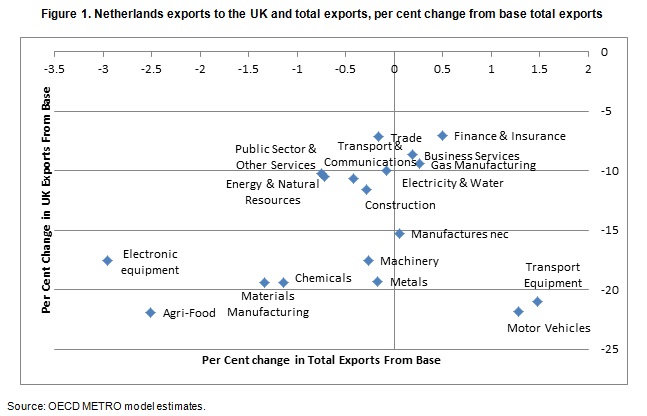

Simulation results show that Dutch exports to the UK would fall by 17%in the medium-term. The Dutch agri-food sector is estimated to experience a 22% fall in its UK exports (Figure 1). This is driven by a substantial 35% decline in exports in the meat products sector. Smaller materials manufacturing sectors such as wood and leather products and textiles would see a 20% fall in their UK exports. The 2% fall in production in agri-food contributes to a 7% decline in the value of agricultural land. Four of the five sectors that record the largest declines in employment following production falls are in the agri-food sectors.

Of all the non-agri-food sectors, electronic equipment would see the largest decline in total exports at 3% and the largest decline in production at 2.4% in the scenario. Access to supply chains for intermediate imports from the UK for Dutch sectors is also curtailed; intermediate imports from the UK would fall by over 40% in the finance and insurance sector in the scenario.

There are a few sectors which have export gains under this scenario. These include motor vehicles, finance and insurance and transport equipment, these sectors show increases in exports to the rest of the EU as well as the United States. The gas sector expands slightly, but this translates into relatively larger gains of gross exports of 6% (to EU) and 10% (to US).

[1] OECD METRO model data.

[2] This shock implies a scenario could be the result of a disorderly conclusion to negotiations and can be considered something close to a worst case outcome and does not consider the impact via investment.

References

OECD (2018), OECD Economic Surveys: Netherlands 2018, OECD Publishing, Paris.

OECD (2015), “METRO v1 Model Documentation”, TAD/TC/WP(2014)24/FINAL.

Vandenbussche, Hylke and Connell Garcia, William and Simons, Wouter, Global Value Chains, Trade Shocks and Jobs: An Application to Brexit (September 2017). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3052259 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3052259