Making housing more affordable in Portugal

By Timo Leidecker, Antoine Goujard and Aida Caldera-Sanchez, OECD Economics Department

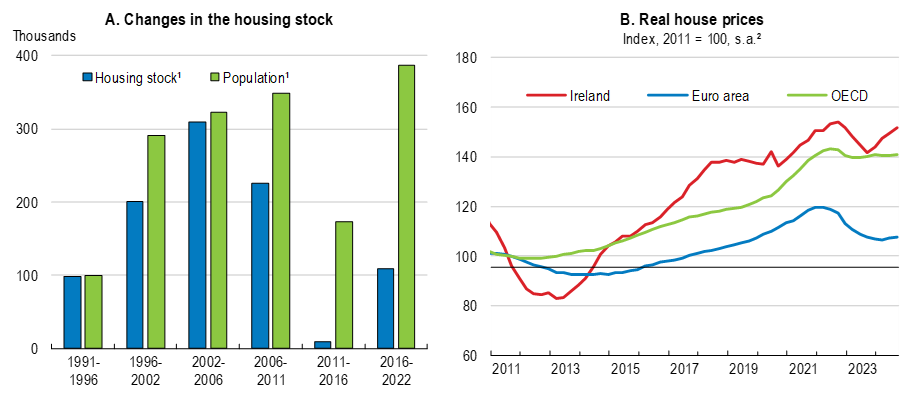

Being a young adult or family in Portugal looking for a home is difficult. For many it has become seemingly impossible to find an affordable home to buy or rent: 44% of respondents in a 2023 survey considered leaving Portugal due to difficulties to find affordable housing (Azevedo and Santos, 2023). After house prices have doubled over the last decade, well outpacing incomes, high housing costs eat into people’s living standards, prevent young people from starting a life on their own, or from going after promising jobs and career prospects if they live far away from where jobs are concentrated (Fig. 1).

Portugal’s housing pressures did not emerge overnight and cannot be blamed solely on the spread of short-term rentals or golden visa programmes. They result from several, long-standing issues: a collapse in construction during the economic crisis, high construction costs, a high share of Portugal’s large housing stock lying idle or only being used ineffectively, and inadequate housing support – all amplified in recent years by rising domestic as well as foreign demand.

What can be done? Successive governments have taken welcome steps aimed at expanding housing supply and support, including through tax exemptions for young first-time buyers and investments in social housing. Yet, as the 2026 OECD Economic Survey of Portugal argues, more decisive action is needed to deliver an effective and lasting solution. The OECD Survey identifies additional reform priorities, including to cut red tape in construction, strengthen fiscal incentives to mobilise existing housing, and provide more well-targeted housing support.

Boosting new construction and making better use of existing housing

New housing supply is held back by high construction costs, including from complex administrative procedures. Digitalising procedures and harmonising requirements for building permits across municipalities would speed up procedures and reduce uncertainty – particularly for smaller firms. High land prices further limit affordability. While recent reforms simplified access to land mostly for social housing, a broader review of spatial planning is needed to remove barriers to sustainable development more generally.

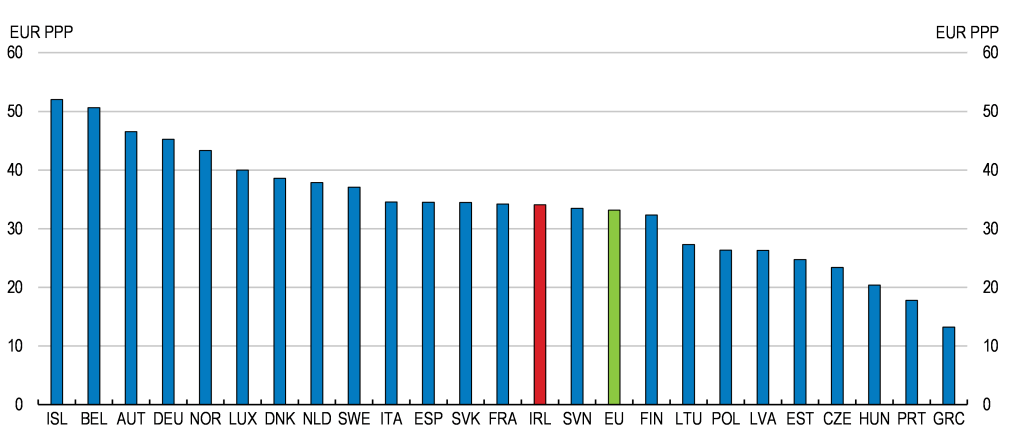

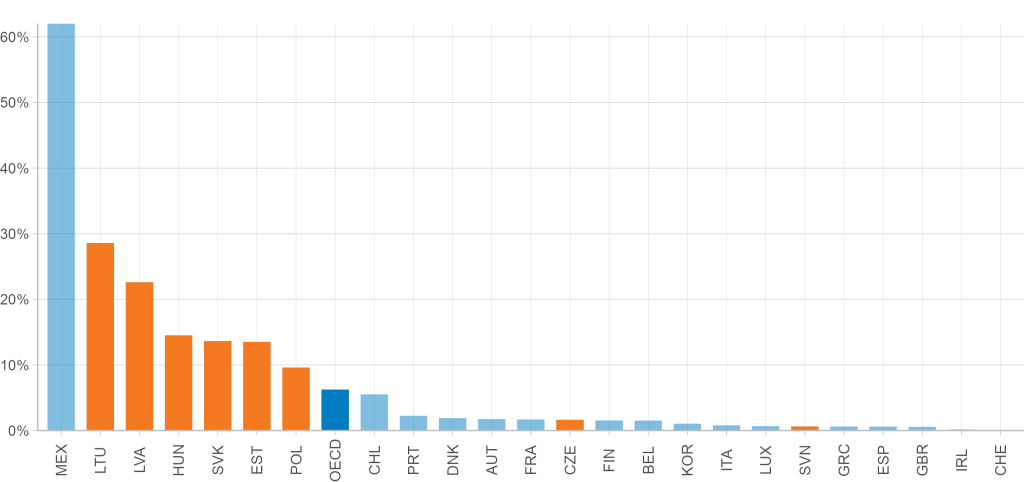

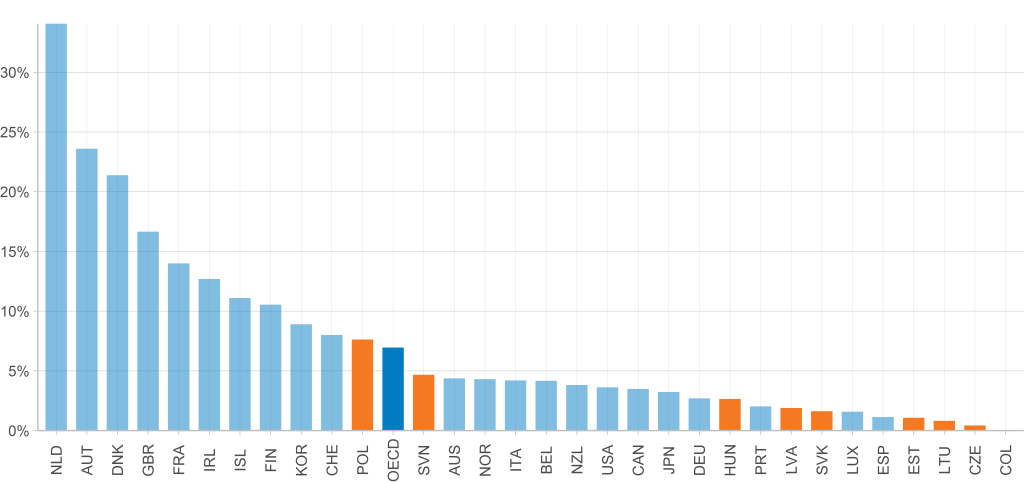

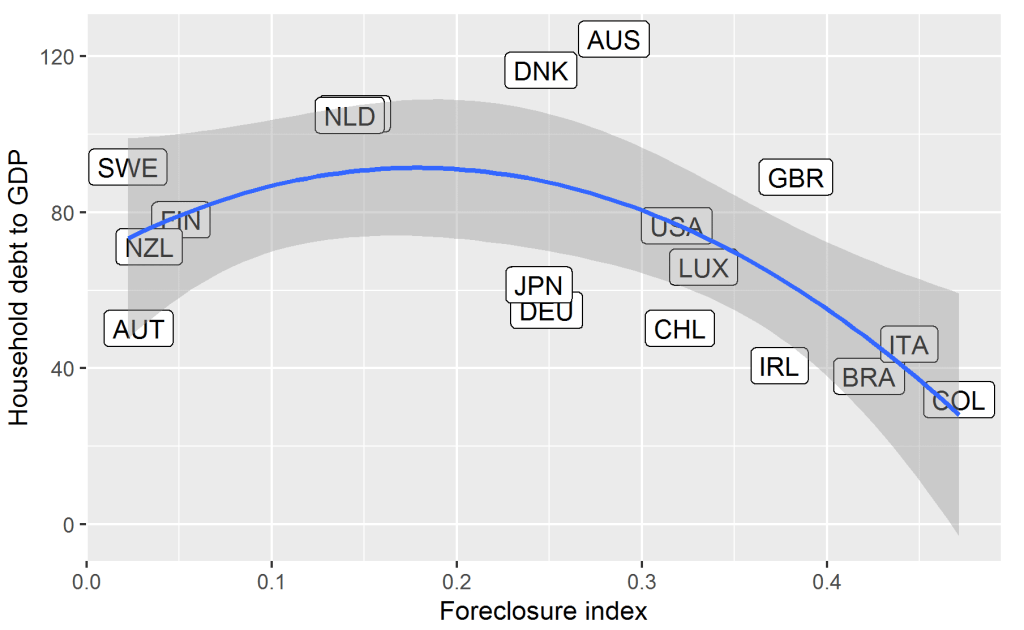

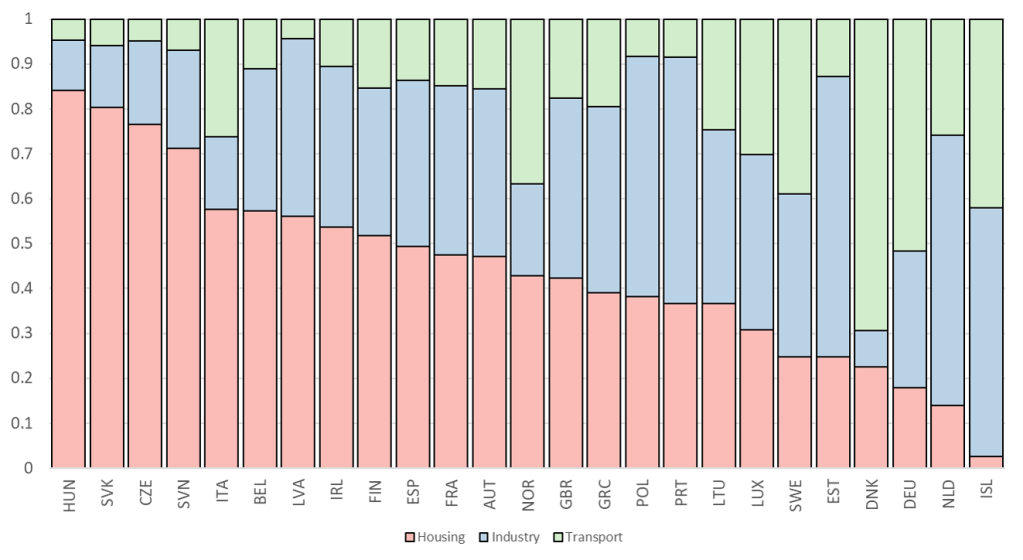

At the same time, fiscal incentives to use existing housing more effectively remain weak. Recurrent property taxes are low, including for those who rarely if ever use or rent their home. Transactions taxes are relatively high for households wishing to buy or downsize (although these were mitigated for young people through transaction tax exemptions). Outdated property tax values are a key contributing factor for the low effective recurrent taxation of housing wealth (Fig. 2). These features help explain the high share of vacant or seasonal homes across the country – even in high-demand areas – and mean that long-standing homeowners have often benefited from largely untaxed capital gains, while younger generations struggle to enter the market.

Gradually shifting from transaction towards recurrent taxes of immovable property, and raising taxation on underutilised housing where demand is high, would help bring more homes onto the market. Regularly updating taxable property values to reflect market prices would strengthen these incentives and improve equity.

Figure 2. Updating tax property values would strengthen fiscal incentives to use housing efficiently and improve equity

Note: Panel A: The OECD average is computed based on preliminary data. Data for Greece are missing. A selection of OECD countries is shown.

Source: OECD Revenue Statistics (database); Eurostat..

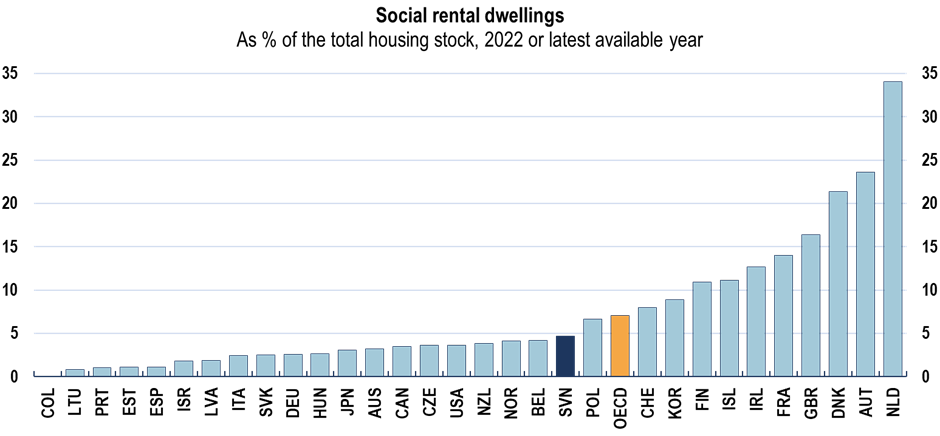

Scaling up social housing and housing allowances

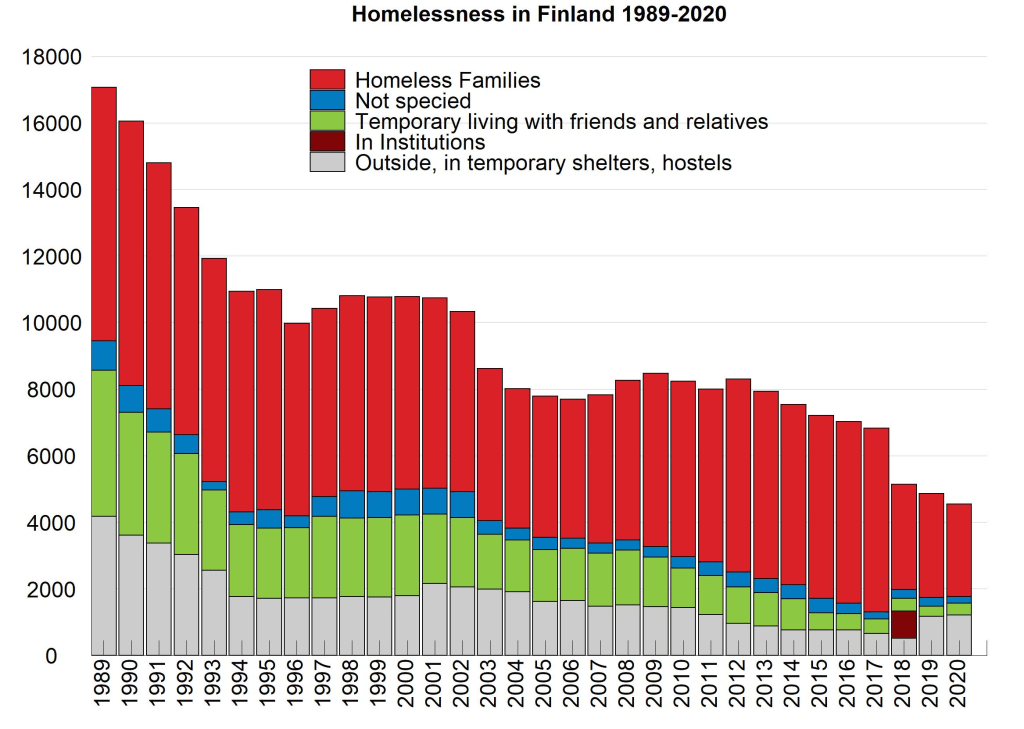

Even with more flexible housing markets, many households will remain unable to afford adequate housing at market prices. Portugal has one of the smallest social housing stocks of the OECD (Fig. 3), and waiting lists for social housing are long – exceeding three years for example in Porto. Investment is increasing but further expansion will be needed. Given municipalities central role, this will hinge on providing targets adapted to local needs and ensuring adequate funding.

As long as social housing remains scarce, housing allowances in the private rental market will play a crucial role. Current spending – at around 0.1% of GDP in 2022 – is limited and aimed reaches more households with high incomes than low-income households. Better targeting and ensuring adequate benefit levels are essential to ensure access to decent housing while containing fiscal costs.

A coordinated reform package is essential

Portugal’s housing affordability challenge is solvable—but only through a comprehensive reform package. Because the underlying causes are deeply interconnected, isolated measures risk being ineffective or counterproductive. Expanding housing support without boosting supply can push prices even higher; rebalancing rental regulations without adequate allowances can increase hardship. Reducing supply constraints would, in turn, lower construction costs, including for social housing, while making private rental investment more attractive.

Implemented together, the reforms proposed in the OECD Survey—to expand supply, mobilise existing housing, and strengthen housing support—can help restore better functioning housing markets. As a package, they would help ensure that everyone can find a suitable home they can afford—an outcome that is key not only to Portugal’s economic prosperity, but to its social and generational fabric.

For more information, visit the Portugal Economic Snapshot page.

References:

OECD (2026), OECD Economic Surveys: Portugal 2026, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/abc5c435-en.

Azevedo, A. and Santos, J. (2023), Housing Barometer, Francisco Manuel dos Santos Foundation https://ffms.pt/sites/default/files/2023-11/BarometroHabitacao-v7.pdf