Doombot versus other machine-learning methods for evaluating recession risks in OECD countries

by Thomas Chalaux and David Turner

Predicting when a recession will hit is no easy task, and economists have long tried to make sense of a wide variety of financial and business cycle data from both domestic and international sources. The challenge of picking the right variables for each country and time frame, which can take on different functional forms, makes machine-learning methods especially useful.

Recent OECD research has compared traditional machine-learning models, including the popular LASSO (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator), with a new algorithm the OECD researchers developed called “Doombot.” LASSO works by simplifying models, helping to improve their accuracy by limiting unnecessary variables. Doombot, however, takes a more exhaustive approach, testing a wide range of variables and placing restrictions to ensure its predictions better align with an overall economic story.

What data was used?

The OECD research tested several algorithms on data from 20 OECD countries, looking at how well they could predict recessions at different time frames, from immediate quarters to two years ahead. The most frequently picked data were financial indicators, such as credit, house prices, share prices and interest rates (like the yield curve slope). Economic activity data, like GDP and unemployment, were used more often for shorter-term forecasts. Notably, these predictors weren’t limited to each country’s domestic economy; international aggregations of the same variables played a significant role.

Doombot performs best on predictive accuracy

When predicting rare events like recessions, it’s important to test models on data they haven’t seen before—this is called “out-of-sample” testing. This helps avoid overfitting, where a model looks good on historical data but performs poorly when making real-time predictions. Doombot outperformed the competition across multiple metrics when tested on OECD countries. In particular, it gave a clearer early warning of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis (GFC) than LASSO and other methods. By rolling forward predictions and comparing across different countries and timeframes, Doombot consistently ranked higher than other models.

Doombot tells a better economic story

In addition to being more accurate, Doombot’s predictions align better with economic narratives. It uses fewer variables—typically less than three per equation—compared to LASSO, and its predictions are more consistent across countries. The signs on the variables (indicating whether a variable should increase or decrease recession risk) are in line with economic logic, which isn’t always the case with other algorithms. Furthermore, Doombot produces smoother recession probability forecasts, avoiding the erratic jumps seen in some other models. These features make it easier for economists to break down the drivers of recession risk and spot trends across different countries.

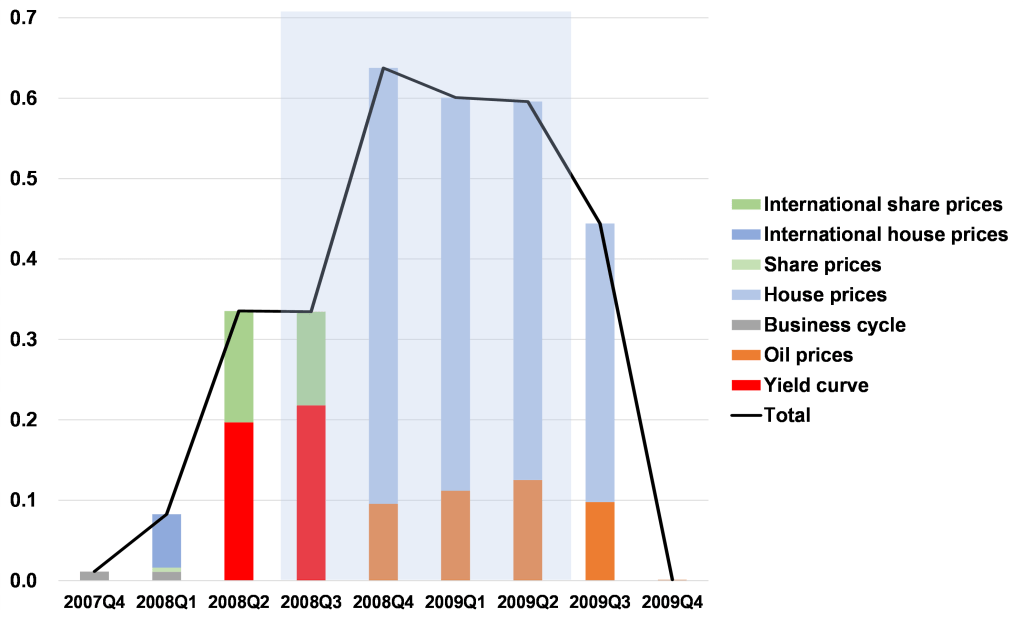

For example, ahead of the GFC, Doombot predicted a steady rise in recession risk for the United States, primarily driven by an inverted yield curve and falling stock prices (see Figure 1). In the longer term, declining house prices and rising oil prices also played a role. Similar patterns appeared in other countries, with house prices and credit developments standing out as key factors leading up to the GFC.

Figure 1. Contributions to predicted recession probabilities for the United States ahead of the GFC

Out-of-sample projections made with data available in early December 2007

Note: This chart shows an approximate decomposition of the recession probabilities into the contribution from each explanatory variable. The predictions are made with the Doombot algorithm using data available in early December 2007. The United States was in recession from 2008 Q3 to 2009 Q2, corresponding to the shaded background area.

The benefits of combining accuracy with narrative

The constraints imposed on the Doombot algorithm help to provide a more coherent economic narrative and so mitigate the common ‘black box’ criticism of machine-learning methods. Perhaps the most interesting and important finding from this work is that there is no trade-off between predictive performance and better story-telling, so that imposing judgmental constraints consistent with economic priors tends to improve rather than hinder the predictive performance of Doombot. This could have important implications for future machine-learning applications in economics.

References

Chalaux, T. and D. Turner (2024) , “Doombot versus other machine-learning methods for evaluating recession risks in OECD countries”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1821, OECD Publishing, https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/doombot-versus-other-machine-learning-methods-for-evaluating-recession-risks-in-oecd-countries_1a8c0a92-en.html