The OECD Energy Support Measures Tracker: Looking back to move ahead

By Cassandra Castle, Assia Elgouacem, Giuliana Sarcina, Enes Sunel, and Jonas Teusch

In the past few years, the global economy has experienced two major crises: the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine. The recovery from the pandemic and the war have both amplified tensions in the energy sector and provoked a surge in energy prices.

The fiscal response to the energy crisis has been large, especially in Europe

The OECD Energy Support Measures Tracker, released on 6 June 2023, shows that in 2022, support measures in response to higher energy prices had a gross fiscal cost of 0.7% of GDP in the median OECD economy, rising to over 2.5% of GDP in some European countries (Figure 1). By way of comparison, these costs exceed what the median OECD country spends on unemployment benefits and are about half of the expenditure on family and child benefits. Comparable levels of fiscal support are foreseen for 2023 in the OECD as a whole. However, the actual cost of support will heavily depend on the evolution of energy prices.

The OECD Energy Support Measures Tracker provides comprehensive data and information on energy-crisis related fiscal support measures

Documenting the measures governments have implemented to face the energy price shock and being able to compare them across countries, remains critical to improving support policies and building resilience against future crises. The Tracker systematically catalogues support measures in place from February 2021 to May 2023 in 41 countries – 35 OECD countries and 6 non-OECD economies (Brazil, Bulgaria, Croatia, India, Romania and South Africa).[1] The data have been collected and processed by OECD country, fiscal and energy policy experts and validated by national administrations.

The new dataset provides granular information to comprehensively characterise individual support measures. These include start and end dates, gross fiscal costs, type of support and delivery mechanism, main beneficiaries of the measures (indicating whether vulnerable households or firms from specific sectors are targeted, and, where applicable, summary information on the differentiation of support between beneficiaries) and the impacted energy carriers (such as diesel, gasoline, electricity, natural gas). The sheer number and diversity of the measures makes classification challenging.

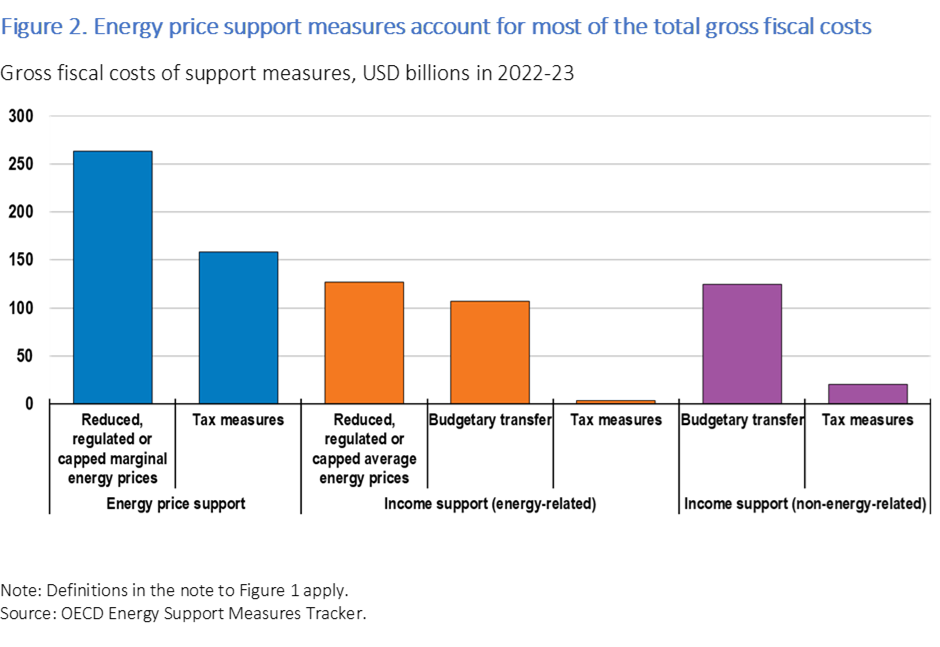

The Tracker classifies more than 550 support measures into two main categories: (1) price measures (e.g. reduced energy taxes and energy price caps), estimated to cost USD 422 billion in 2022-23; and (2) income measures (e.g. transfers and tax credits to consumers), estimated to total USD 383 billion in 2022-23. Within income measures, a distinction is made between measures that reduce the average price of energy in consumers’ energy bills and measures that are unrelated to the level of energy consumption (Figure 2).

The measures – which were implemented swiftly amidst uncertainty, political economy constraints, and a focus on administrative simplicity – affect the behaviour of firms and people in different and significant ways, and may contribute to or detract from important longer-term policy objectives. Income support can maintain incentives to save energy whereas price measures weaken them, propping up demand for fossil fuels and effectively acting as a negative carbon price. Among income measures, those that are unrelated to the level of energy consumption tend better to preserve incentives for energy efficiency improvements than those that reduce the average price in the energy bill paid by consumers.

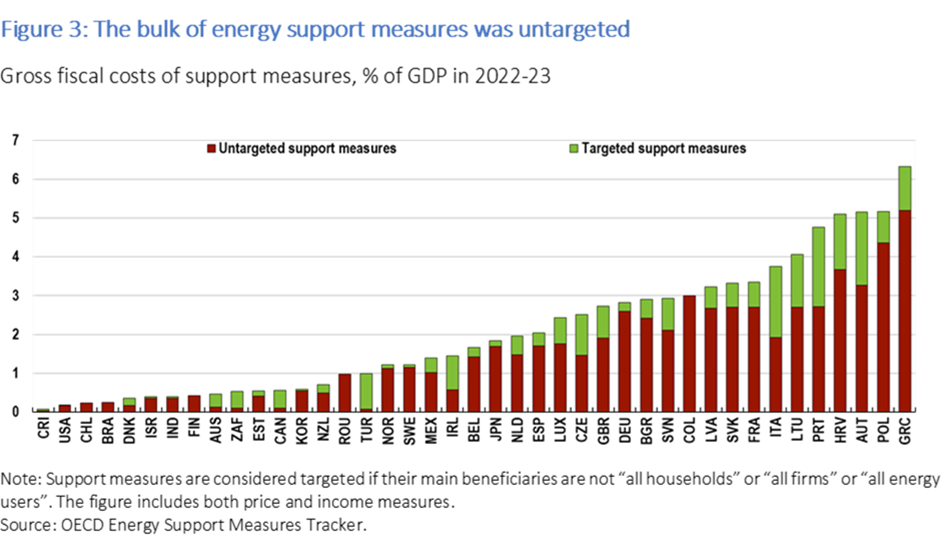

Measures were rarely targeted and increased the incentive to consume fossil fuels

Untargeted support measures make up the majority of the estimated total cost of support in 2022-23 (Figure 3). Among these, energy price support measures account for over 50% of total spending and carry substantial non-fiscal implications. While price support measures are straightforward to design and often politically popular, they weaken incentives to save energy and are rarely targeted (over 92% of energy price support measures are untargeted), meaning that they tend to disproportionately support better-off households.

Click for Chart data

A clear taxonomy of measures and data can enable the design of better energy support policieswhen they are needed

Energy prices are receding, but possible renewed tensions in energy markets due to geopolitical developments and bottlenecks along the energy transition may result in higher energy price volatility in the future. Preparing government policy for possible new energy price spikes requires data and information on how support measures affect the behaviour of households and firms, their impact on public finances and their unintended consequences. The OECD Tracker is a resource for policymakers to do just that.

More information

OECD (2023), OECD Energy Support Measures Tracker, OECD database available at:

OECD (2023), “Aiming Better: Government Support for Households and Firms During the Energy Crisis”, OECD Economic Policy Papers No. 32, OECD Publishing: Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/839e3ae1-en

[1] The government of Iceland has not taken any energy support measures. The Tracker also includes information on another five countries, for which it was either not possible to quantify the gross fiscal cost of the energy support measures (Argentina, China, Hungary and Indonesia) or these were deemed to have no impact on budget deficits, as is the case of measures providing credit and equity support (Switzerland).