Towards net zero emissions in Denmark

By Andrew Barker, Hélène Blake and Patrick Lenain, OECD Economics Department

Denmark has embarked on an impressive climate policy agenda with ambitous emissions targets, carbon pricing, innovation, public investment and regulatory policies. The share of renewables in electricity generation has grown from less than 10% in the mid-1990s to over 80% in 2020. This has been the key driver behind the sharp cuts in greenhouse gas emissions by 36% between 1990 and 2019, making Denmark one of the least carbon-intensive countries in the OECD. Emission cuts have been achieved without compromising economic or jobs growth, with progress in wind generation in particular contributing to the development of an important export industry.

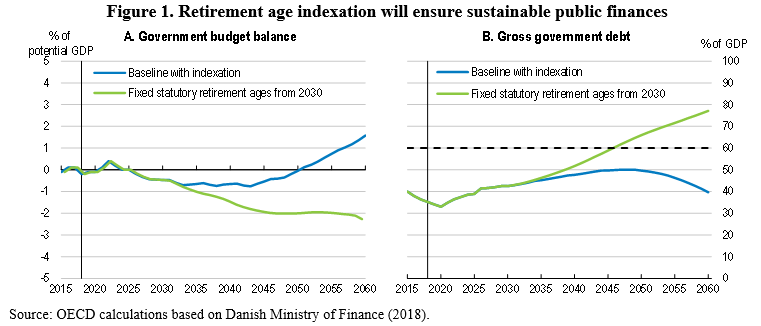

Denmark intends to go further with a a legally-binding commitment to cut emissions by 70% by 2030 from 1990 (Figure 1). This will require halving emissions from 2019 levels – a similar reduction in the next decade as has been achieved in the past 30 years. Cutting emissions at such a fast pace will be challenging, with substantial disruptions and socioeconomic challenges. Radical technological changes and vast resource reallocation will take place throughout the economy, similar to the transformational change in the Danish electricity sector since the mid-1990s. Greater certainty on policy measures to meet these targets will be important to send strong signals to investors. Additional investment in the order of 1% to 2% of GDP will be needed, which could largely come from the private sector with the right incentives.

Job losses to date in high-carbon activities have been offset by new opportunities in green industries – workers with skills in offshore oil and gas have for instance retrained to work in offshore wind. The succesful Danish “flexicurity” system, which combines a safety net with support for skill building and job search, will continue to play a key role to facilitate this sizeable transformation.

Figure 1. Meeting targets will require further progress in all sectors

The energy sector must continue its transition towards renewable sources. Scarce supplies of sustainable woody biomass, on which Denmark has relied for low-emissions district heating, will need to be freed up for the difficult-to-decarbonise sectors, while continuing to protect security of supply as wind generation expands. A low-carbon economy will rely heavily on renewable energy, which can be promoted by further decreases in taxes on renewable electricity, as well as technological breakthroughs allowing large-scale conversion of electricity into sustainable fuels such as hydrogen, methane or ammonia.

Progress in reducing transport emissions has been slow to date, despite more environmentally-friendly vehicles, as the number of cars has continued to increase as well as the reliance on road transport (Figure 2). Agriculture is also a major and growing source of greenhouse gases. Low-hanging fruit such as rewetting of peatlands and improved manure management are available to cut emissions with limited impact on activity, while also reducing other environmental damages. Denmark needs to work with other EU member states towards further reform to green the Common Agriculture Policy, as agriculture is highly exposed to international trade and emissions could increase elsewhere if Denmark proceeds without international cooperation.

Figure 2. Increasing car use has pushed up transport emissions despite greener vehicles

The Danish government has made substantial progress to overcome many of the challenges linked to deep emission cuts. In the past year and a half, for example, the government has removed restrictions in district heating to support a move away from biomass, agreed measures to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in agriculture, and increased support for green vehicles and electric charging infrastructure. Further policy actions are being discussed among various stakeholders, including more uniform emission pricing. Denmark’s past and planned efforts to decarbonise quickly and achieve net zero in 2050 are an inspiring example for other countries, as highlighted in the 2021 OECD Economic Survey of Denmark.