A new aggregate measure of human capital: Linking education policies to productivity through PISA and PIAAC scores

By Balázs Égert, Christine de la Maisonneuve and David Turner, OECD Economics Department.

While human capital is widely regarded as a key driver of economic growth, measuring it is challenging. The empirical literature aimed at constructing a measure of human capital at the country level has combined quantity (such as mean years of schooling) and quality (typically internationally standardised test scores) components either using arbitrary, most often equal, weights or by including them separately in estimations. Results tend to show, surprisingly, that one component is dominant and the other completely insignificant. A further weakness of many studies that try to incorporate notions of quality into measures of the human capital stock is that they are based on contemporaneous flow measures that most often relate to students tested at age 15, which are unlikely to be representative of the skills of the entire (and older) working age population.

Our recently published working paper: A new macroeconomic measure of human capital exploiting PISA and PIAAC: Linking education policies to productivity (Égert et al, 2022) addresses these two weaknesses by constructing a new stock measure of human capital that makes use of OECD data from the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) and the Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC). Improving aggregate measures of human capital is important given the central role that education, training and skills play as a driver of economic performance.

A new aggregate stock measure of human capital

The new measure is a cohort-weighted average of past PISA scores (representing the quality of education) of the working age population and the corresponding mean years of schooling (representing the quantity of education). Contrary to the existing literature, the relative weights of the quality and quantity components are not imposed or calibrated but are estimated directly. Our calculations involve three stages.

- First, a matching is established between PIAAC adult test scores, mean years of schooling and PISA student test scores of the corresponding cohort who took the student tests as 15-year olds. Such matching is reasonable given that both PIAAC and PISA tests capture similar skills: PISA scores cover reading, maths and science; PIAAC adult test scores cover literacy, numeracy and problem solving.

- Second, PIAAC test scores are regressed on matched PISA test scores and mean years of schooling. The estimation results show that the elasticity of the stock of human capital with respect to the quality of education is three to four times larger than for the quantity of education.

- Third, these estimated elasticities are used to construct an aggregate time series stock measure of human capital by cumulating quantity and quality measures across all cohorts in the working age population.

This approach relies on combining data from both PISA and PIAAC in order to overcome inherent problems with using either in isolation. On the one hand, PIAAC provides a measure of skills for the entire adult working age population, but has no time series and limited country coverage, hence ill-suited for empirical regression analysis. On the other hand, PISA only applies to those aged 15 but, very importantly, especially when combined with similar international test scores, has a more extensive time series and country coverage.

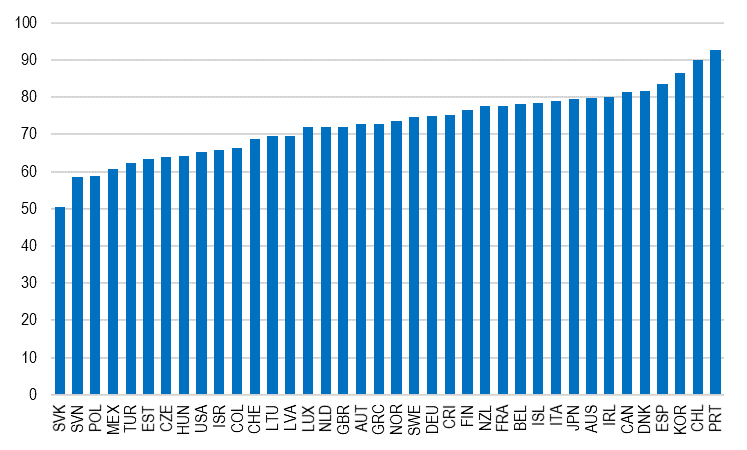

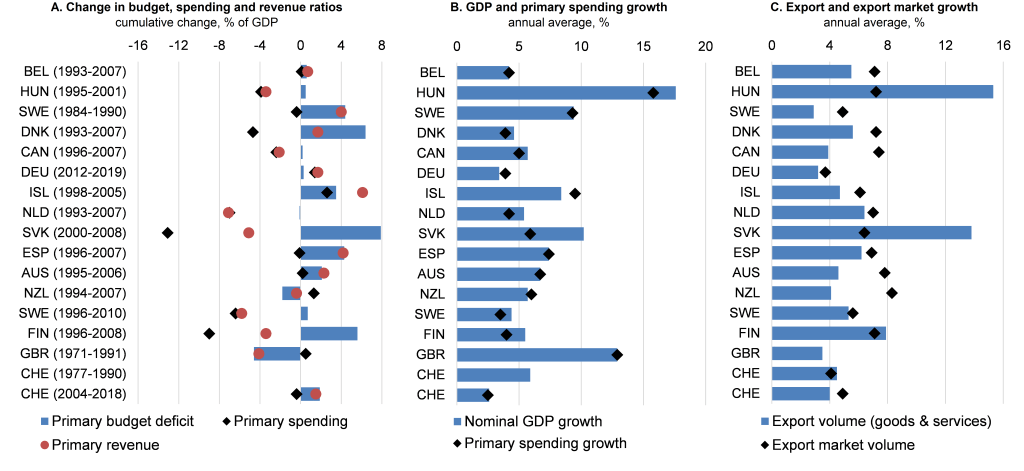

The new measure of human capital for the population aged 16 to 65 years suggests that the countries with the greatest human capital include Australia, Japan and Finland, while Chile and Thailand have the lowest levels of human capital among this group of 16 countries (Figure 1, Panel A).1 These rankings for the last available year are broadly confirmed for the stock covering the population aged 16-39 (Figure 1, Panel B), although there are some differences suggesting that younger generations have been increasingly better educated in some countries than in others. For instance, Finland lags behind Japan for the total stock, but the countries flip places for the stock covering only the younger generations, because the stock of human capital of younger generations has risen more strongly in Finland compared to Japan.

Figure 1. The new measure of the stock of human capital

Human capital effects on productivity are potentially large but come with long lags

The new measure of human capital shows a robust positive correlation with productivity for OECD countries in cross-country time-series panel regressions, suggesting that improvements in human capital are accompanied by macroeconomic productivity gains.

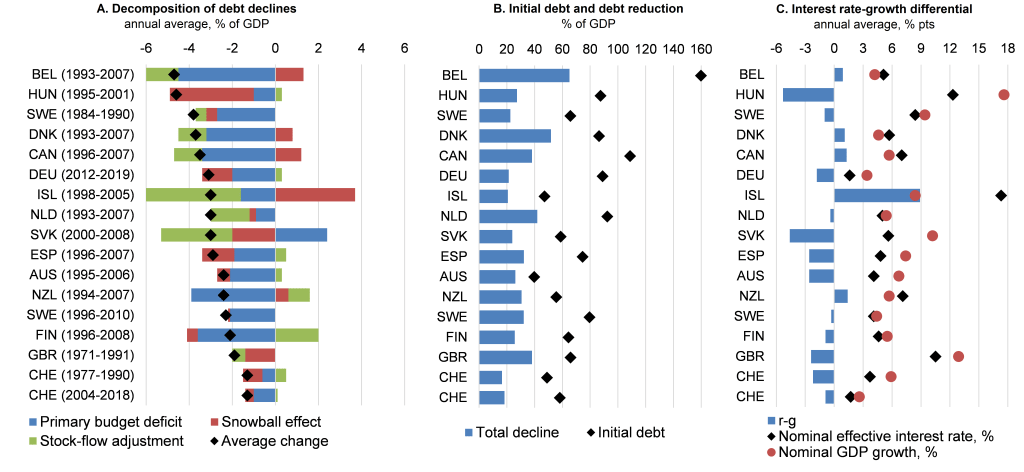

Simulations suggest that the potential for long-run productivity gains is much greater from improvements in the quality than the quantity component of human capital. An improvement in PISA test scores, equivalent to closing the gap between the median and the top three performing OECD countries, eventually generates a long-run increase in multi-factor productivity (MFP) of between 3.4% and 4.1%. Alternatively, a similar increase in mean years of schooling, also corresponding to reducing the gap between the median and the top three performing OECD countries, generates an increase in TFP of between 1.8% and 2.2%.

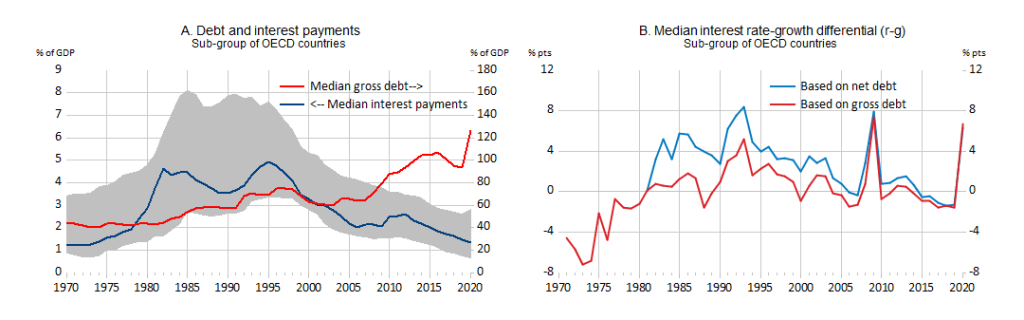

Another finding is that gains in productivity through the human capital channel can be of the same order of magnitude as from improving product market regulation, again using the same benchmark of closing the gap between the median and the top three performing OECD countries. The lags are, however, also typically much longer from the human capital channel, particularly because it takes almost five decades before a sustained improvement in student skills are fully reflected in improvements in the skills of the entire working age population (Figure 2). These long lags can be shortened by putting more emphasis on adult learning including life-long learning and upskilling of the existing workforce, improving human capital at older ages.

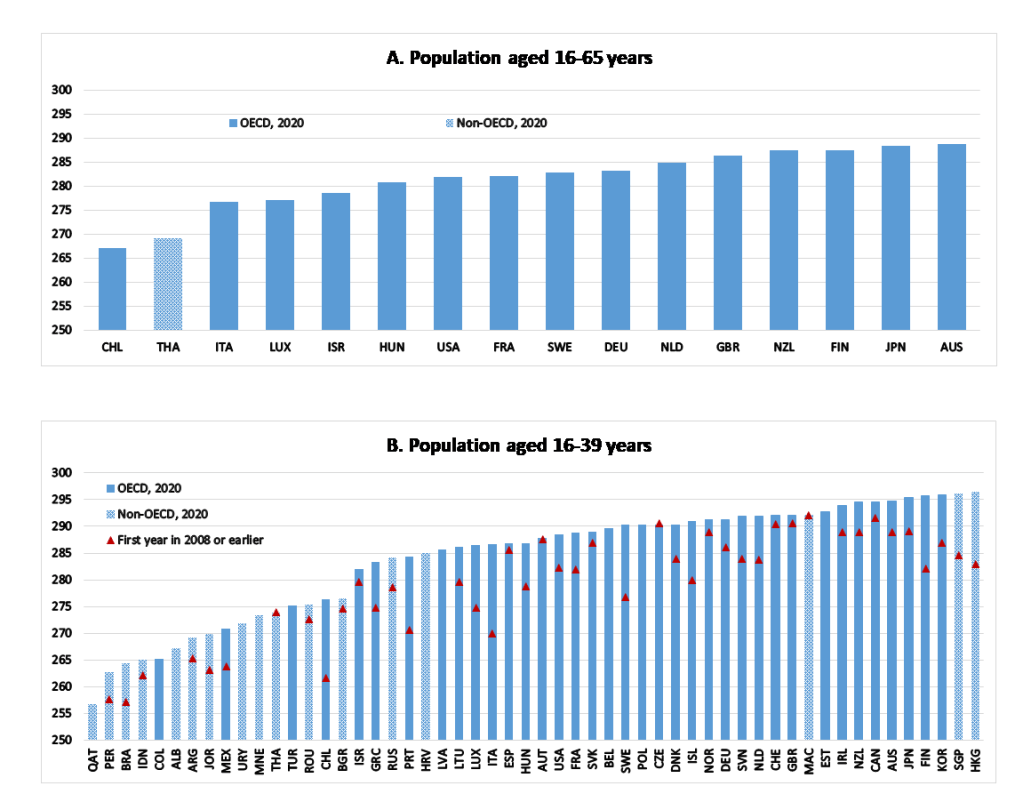

Figure 2. Comparing policy responses to improve skills and product market competition

Change in multi-factor productivity, per cent

Assessing the effect of education policy reforms on human capital and productivity: the illustrative example of pre-primary education

An attractive feature of the new stock measure of human capital is that it opens up new avenues for evaluating the effect of education policy reforms on productivity and per capita income. Any education policy, which can be measured quantitatively through an indicator and linked to changes in student test scores, can be related to the new measure of human capital and so to productivity.

We use pre-primary education as an illustrative example. The first step in the quantification of the effect of pre-primary education attendance may be provided by the existing empirical literature using microeconomic student-level data, which finds that students previously enrolled in pre-school for more than one year perform better in student skill tests, improving their test scores by between 8.2 and 9.6 points. This corresponds to an increase of 1.7% to 1.9% compared to the OECD median PISA score in 2018.

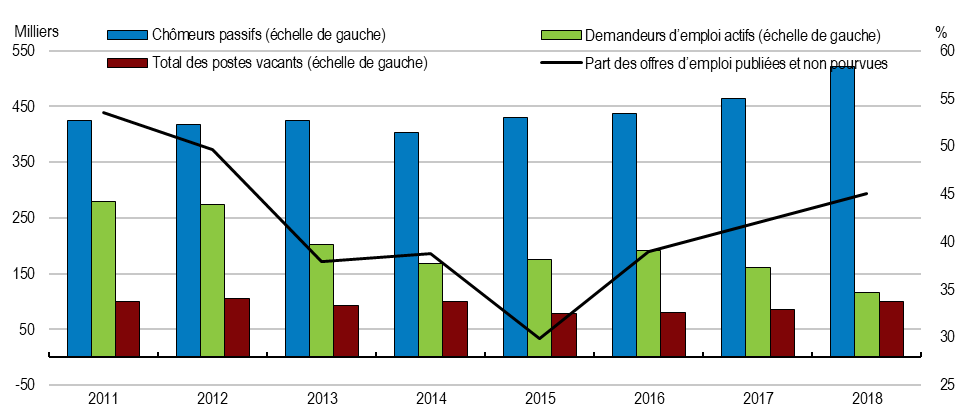

In order to assess the policy effects on the stock of human capital and multi-factor productivity from reforming pre-primary education, two scenarios are considered: i.) closing the gap between the lowest level of pre-primary attendance observed in the OECD (9% in Turkey) and the average of the top three performers (84%, Spain, France and New Zealand), and ii.) closing the gap between the median OECD country (72%, Austria) and the average of the top three performers. Results indicate that a sustained effort to increase attendance in pre-primary education boosts productivity in the long run between 0.9% and 2.2% for the first scenario, and gives rise to a more limited increase of 0.1% to 0.3% in the second scenario.

Future work will focus on a systematic evaluation of a wide range of education policies on the new measure of human capital and macroeconomic outcomes as well as considering how adult training policies impact on human capital.

Reference

Égert, B., C. de la Maisonneuve and D. Turner (2022), “A new macroeconomic measure of human capital exploiting PISA and PIAAC: Linking education policies to productivity”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1709, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/a1046e2e-en.

[1] There are a limited number of countries with a sufficiently long time series of student test scores to be able to construct the measure for the full working age population. This implies a trade-off. A comprehensive measure covering the entire working age population can only be computed for 15 OECD countries. A measure covering those aged 16 to 39 is available for a total of 54 OECD and non-OECD countries in the last available year, and 12 countries have data series for more than 20 years and an additional 27 countries are covered for about a decade.