Preparing for better times: Chile’s policy priorities for an inclusive recovery

By Paula Garda and Nicolas Ruiz, Economics Department

Over the past 20 years, Chile has made tremendous progress towards greater economic prosperity, more than doubling its per capita income while lifting many Chileans out of poverty. Such achievements have come to a halt during 2020 as Chile has faced two unprecedented shocks: the social protests of end 2019 and the COVID-19 outbreak. Those shocks have plunged Chile into a recession with a magnitude unseen since the 1982 monetary crisis. The policy reactions to the pandemic have been swift and bold to cushion an unprecedented shock for the households and firms. However, as Chile is heading towards a gradual recovery from the pandemic, there is a pressing need for more profound economic and social transformations to achieve a recovery shared by all, putting Chile on a more inclusive and sustainable growth path.

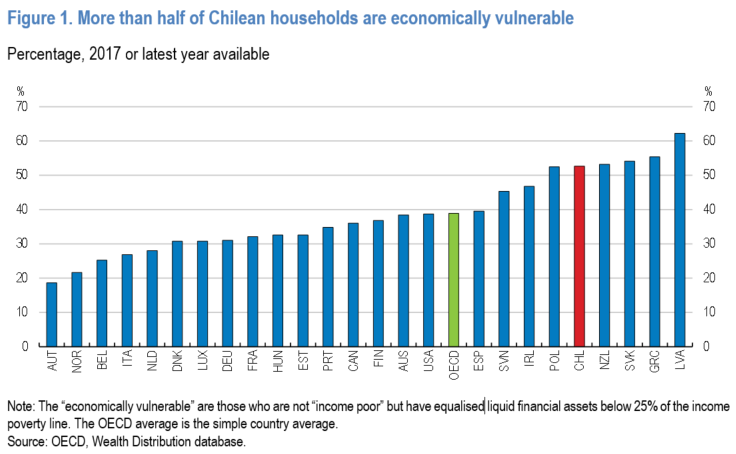

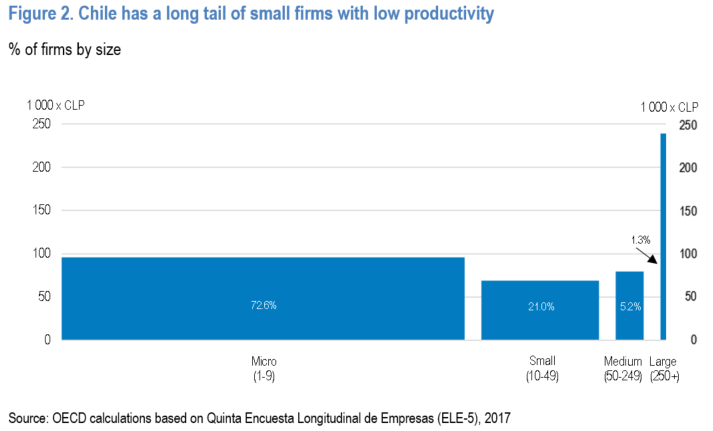

Chile must fill its twin missing middles: a weak middle class, and a lack of dynamic midsize firms, making Chile’s middle class weak overall. More than half of Chilean households are economically vulnerable. Those are households not counted as poor but are at risk poverty, due to low income and a lack of sufficient minimum wealth to cope with an adverse income shock (Figure 1). Many of these households might have fell into poverty during 2020. At the same time, Chile exhibits a persistent division between a small number of large and productive firms and a long tail of small and midsize companies with considerably lesser productivity performance (Figure 2). Such productivity polarization tends to sustain a vulnerable middle-class: the scarcity of higher-productivity and higher-wage jobs generates informal and precarious jobs, associated with low social protection and low, unstable income, amplifying the risk of falling back into poverty in a recession or in the event of a health crisis.

The survey identifies policy priorities for a successful recovery and to build a strong and prosperous middle-class in Chile. These measures and reform areas include:

- Stepping-up the efficiency of the tax and transfer systems: The tax and transfer system barely reduces inequality. The base of the personal income tax is too narrow and broadening it after the recovery is well on its way would raise needed revenue. In return, the extra resources can be devoted to the creation of a negative income tax, which would assure each household and individual a basic benefit.

- Promote access to quality education for all: Access to good education remains strongly linked to the socio-economic status of the family. Spending on education should be stepped-up and prioritized on high-quality early childhood, primary and secondary education, as a prerequisite for raising skill levels and expanding tertiary education. While the effects of these policies will be felt only in the long run, it constitutes a pivotal lever to fight now the consequences that COVID-19 could imprint on inclusiveness and inequality of opportunities.

- Increase the relevance and quality of training: Access of vulnerable workers to training courses is insufficient and many of their job profiles might change in the future or even disappear with automation risk. Training programmes should be reviewed to increase quality and relevance and target those that need it the most ensuring that all workers, particularly the most vulnerable, have adequate opportunities for retraining and finding good-quality jobs.

- Generalize zero-licensing procedures: The regulatory environment inhibits competition and the scaling up of firms. Generalizing “zero licensing” by involving municipalities in the design of the initiative could ease firm entry and formalization, which could contribute to reducing inequalities over time by creating better paying jobs.

- Boosting the digital transformation: The crisis highlighted disparities in digital skills and technology access and use among Chilean students, workers and firms. One of the biggest challenges is the access to high-speed broadband internet, particularly in rural areas. Lower entry barriers in the communication sector could accelerate both fixed and mobile network deployment and improve access to high-speed broadband services at competitive prices. Stepping up digital skills and firms’ adoption of digital tools, mainly SMEs, would help workers and firms in the transition to a swift recovery. Chile needs better integrating digital skills in school and enhancing teacher training. More targeted programmes for the adoption of digital tools and the development of financing instruments, notably for SMEs, designed in close collaboration with the private sector, would allow them to adopt digital tools.

More information:

OECD (2020), OECD Economic Surveys: Chile 2020, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/79b39420-en