Shocks, risks and global value chains in a COVID-19 world

by Frank Van Tongeren, OECD Trade and Agriculture Directorate

In just six short months, the COVID-19 pandemic has swept the globe, leaving but a few island nations untouched. The virus and the measures required to contain it have left in in their wake a global economy damaged beyond what was thought possible after the financial crisis over a decade ago. Unemployment in the OECD area increased by an unprecedented 2.9 percentage points in April alone, up from 5.5% the previous month, and the recent OECD Economic Outlook projects that ‘five years or more of income growth could be lost in many countries by the end of 2021’. The pandemic has painfully reminded us of the vulnerability of the global economy to unexpected shocks.

In the early stages of the pandemic, we saw dramatic shortages in the global availability of personal protective equipment and other medical supplies due primarily to surging demand, in some cases exacerbated by trade restricting measures. This raised questions about whether the relative gains and risks from deepening and expanding international specialisation in global value chains (GVCs).

Global value chains organize the cross-border design, production and distribution processes, creating much of what we purchase and consume every day: from food and medicines to smartphones and cars. Some people now wonder whether more localised production of key goods would provide greater security against disruptions that can lead to shortages in supply and uncertainty for consumers and businesses.

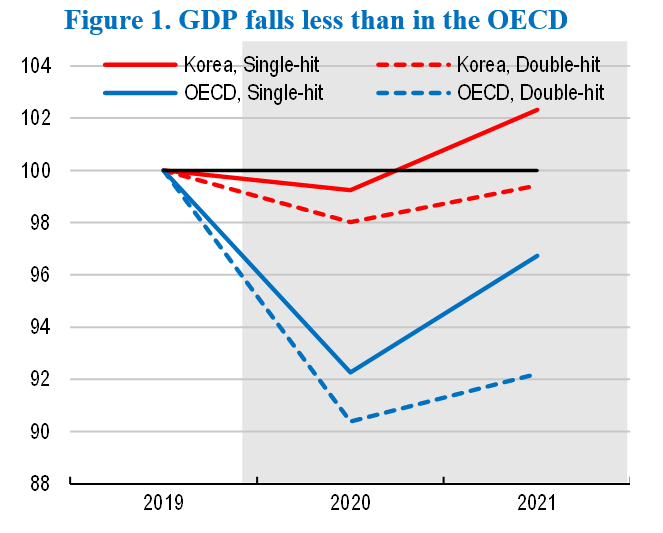

Modelling the question of reshoring post-COVID

While we do not have a more ‘localised’ world at hand that we can use to compare vulnerability to shocks such as the COVID-19 pandemic, we can use economic models to explore such a counterfactual scenario and equip policy makers with information that can help them start to answer these pressing questions. Recent simulations with a large-scale OECD trade model, METRO, compare two stylised versions of the global economy: the interconnected economies regime captures production fragmentation in GVCs much as we see it today, but also taking into account the changes already resulting from the COVID-19 crisis. These include reductions in supply and productivity of labour, reductions in demand for certain goods and services, and a rise in trade costs related to new customs procedures for goods and restrictions on temporary movement of people in services. In the localised -‘turning inward’- regime, production is more localised and businesses and consumers rely less on foreign suppliers. This illustrative counterfactual world is constructed through a global rise in import tariffs to 25%, combined with national value-added subsidies equivalent to 1 % of GDP on labour and capital, directed to domestic non-services sectors to mimic rescue subsidies that favour local production. It is also assumed that, in the localised regime, firms are more constrained in switching between different sources of products they use, making international supply chains more rigid. Those assumptions create strong incentives to increase domestic production and rely less on international trade and are meant to illustrate a range of potential implications of policies that aim at more localisation.

Starting from these two baseline scenarios for future trade regimes, the models can be exposed to a ‘supply chain shock’ similar to the disruption COVID-19 caused to global supply chains. During the pandemic, disruptions to labour, transport and logistics increased the cost of exporting and importing to a similar extent. The analysis, laid out in Shocks, risks and global value chains: insights from the OECD METRO model explores how the interconnected economies and the localised regimes compare in terms of the propagation of, or insulation from such shocks. The ‘supply chain shock’ is simulated with a 10% increase in the costs of bilateral exports and imports between a given region and all other countries. Because a shock that decreases trade costs by 10% –a big drop in oil prices for instance— would have effects of the same magnitude, but in the opposite direction, both the downside and upside stability in the two regimes can be explored.

Increased localisation leads to GDP losses and makes domestic markets more vulnerable

Current debates over future trade regimes often focus on a purported trade-off between efficiency and security of supply. This model simulation study allows us to evaluate the two simulated regimes for both. It found that a localised regime, where economies are less interconnected via GVCs, has significantly lower levels of economic activity and lower incomes. Increased localisation would thus add further GDP losses to the economic slowdown caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, even with the support and protection offered to domestic producers under a localised regime, not all stages of production can be undertaken in the home country, and trade in intermediate inputs and raw materials continues to play an important role in domestic production. In that context, less international diversification of sourcing and sales means that domestic markets have to shoulder more of the adjustments to absorb shocks, and this translates into larger price swings and large changes of production, and ultimately to greater variability of incomes. In this sense, the more localised regime delivers neither greater efficiency nor greater security of supply.

Recent OECD analysis on The face mask global value chain in the COVID-19 outbreak offers an concrete illustration. It showed that producing face masks requires a multitude of inputs along the value chain, from non-woven fabric made with polypropylene to specialized machinery for ultra-sonic welding. While the production itself does not require high-tech inputs, localising the production of just this one good would require high capital investments which would need to be supported during periods when demand shrinks and localized production is not competitive. With current technologies it would therefore be excessively costly for every country to develop production capacity that matches crisis-induced surges in demand and which encompasses the whole value chain from raw materials through distribution for a whole catalogue of essential goods to match any potential crisis—foreseen and otherwise.

More localisation also means more reliance on fewer sources of—and often more expensive—inputs. In this regime, when a disruption occurs somewhere in the supply chain, it is harder, and more costly, to find ready substitutes, giving rise to greater risk of insecurity in supply. This is also the case for sectors that are often seen as strategic: food, basic pharmaceuticals, motor vehicles and electronics.

Work on Trade interdependencies in Covid-19 goods further supports these findings, demonstrating that no single country produces efficiently all the goods it needs to fight COVID-19. Indeed, while the United States and Germany tend to specialise in the production of medical devices, China and Malaysia are most specialised in producing protective garments.

While the argument about GVCs is often posited as one of efficiency versus security, OECD research illustrates that greater localisation fails to achieve either. The localization of production is costly for the most developed countries and virtually impossible for the less developed—while at the same time a localised regime provides less protection from the impact of shocks.

An alternative, more effective and cost-efficient solution to the challenges posed by shortages in some key equipment during demand surges may involve the combination of strategic stocks; upstream agreements with companies for rapid conversion of assembly lines during crises and supportive international trade measures.

If this crisis has taught us anything, it is that viruses, shocks, and economic consequences know no borders, and the one and best option that we have is to meet these challenges together.

References:

OECD Economic Outlook. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 24, June 2020. http://www.oecd.org/economic-outlook/june-2020/

Shocks, risks and global value chains: insights from the OECD METRO model. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 29, June 2020. https://issuu.com/oecd.publishing/docs/metro-gvc-final

The face mask global value chain in the COVID-19 outbreak: Evidence and policy lessons. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 4, May 2020. http://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/the-face-mask-global-value-chain-in-the-covid-19-outbreak-evidence-and-policy-lessons-a4df866d/

Trade interdependencies in Covid-19 goods. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 5, May 2020. http://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/trade-interdependencies-in-covid-19-goods-79aaa1d6/