Fiscal decentralisation and inclusive growth?

by Sean Dougherty, Senior Advisor, OECD Fiscal Network

Over the last decade or more, many countries have experienced slowing productivity growth and a rising concentration of income. Concerns about these developments have motivated a broadening of the policy discussion about how to ensure that economic growth is made more inclusive and multidimensional. One important channel for addressing these concerns is through intergovernmental fiscal relations. By providing the “right” incentives and improving rules and practices in policy making, these institutions can shape fiscal policy and multidimensional outcomes at all government levels. The OECD Fiscal Network has recently published a volume covering these topics.

Over the last decade or more, many countries have experienced slowing productivity growth and a rising concentration of income. Concerns about these developments have motivated a broadening of the policy discussion about how to ensure that economic growth is made more inclusive and multidimensional. One important channel for addressing these concerns is through intergovernmental fiscal relations. By providing the “right” incentives and improving rules and practices in policy making, these institutions can shape fiscal policy and multidimensional outcomes at all government levels. The OECD Fiscal Network has recently published a volume covering these topics.

Design of decentralisation, reform options and the impact on outcomes

Earlier work published in the Fiscal Federalism Studies has shown that the stage of economic development and political economy constraints play important roles in determining the success of fiscal decentralisation. Rather than rely on unique prescriptions, policymakers should consider the importance of institutional complementarities to reap the full potential of fiscal decentralisation. The volume reinforces this message, and demonstrates the importance of considering country specificities in addition to policy design principles when reforming intergovernmental institutions and transfer systems.

Several chapters therein address the basic design of fiscal federalism and associated reforms. One overarching finding is that balanced decentralisation – that is, when the various policy functions are decentralised to a similar extent – is conducive to growth. Similarly, the efficiency of public service delivery in education and health is found to be conditional on sufficient political and institutional capacity. Balanced decentralisation allows sub-national governments to better co-ordinate policy and to reap economies of scale and scope across functions. Moreover, a country’s scope for achieving growth that is also inclusive varies widely depending on its characteristics and its public finance mix.

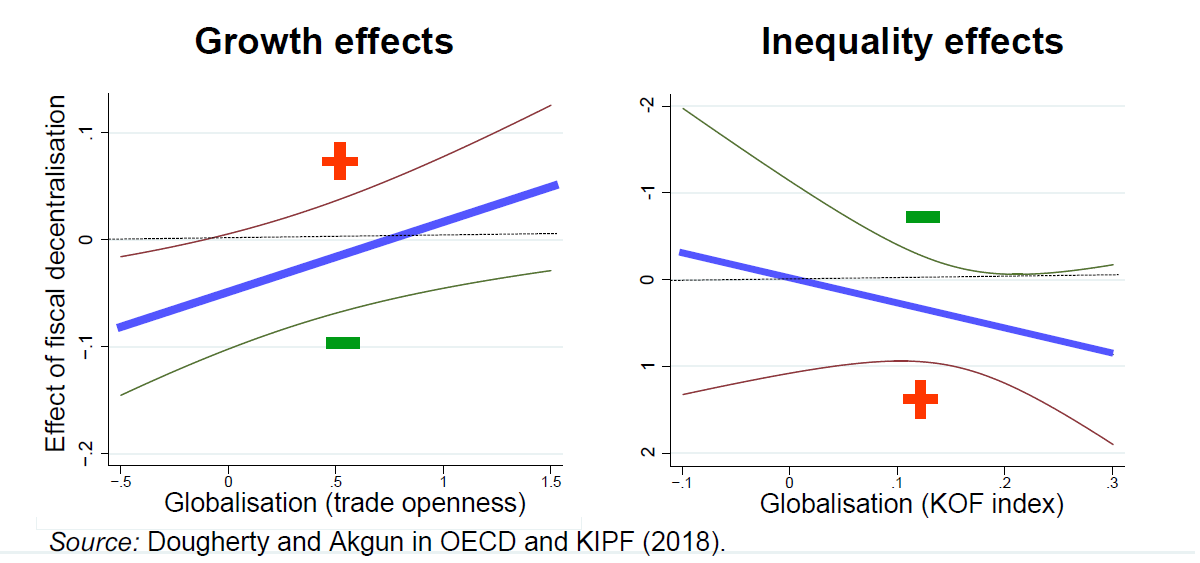

Spending and revenue decentralisation tends to boost economic growth for economies that have a relatively higher degree of globalisation, based on the analysis in this book. Fiscal decentralisation has a more ambiguous effect on inequality than on growth, especially for economies with a higher degree of openness. Moreover, for some countries, there is an apparent trade-off between growth and equity, when it comes to the “optimal” degree of spending and revenue decentralisation.

A potential trade-off between efficiency and inequality is also examined in an analysis of education financing decisions, which looks at the link between local education funding and inequality. However, a range of country-specific policies tend to offset potential trade-offs.

“Design is in the details”

Given the complexity of cross-country results, the chapters include detailed examinations of various aspects of intergovernmental relations in Korea, the Netherlands, India and the United Kingdom. These analyses broadly mirror the cross-country findings, yet they also qualify them in terms of the difficulties in achieving various objectives. For instance, the analysis of Korea’s education financing system finds that it could benefit from more decentralised financing, both in terms of overall outcomes and equity. Empirically, heightened inequality tends to induce more spending on educational opportunitites for lower income populations. This analysis also finds that lower-scoring populations benefit the most from enhanced public educational investment.

Modelling of the Netherlands’ tax system shows that the design of local revenue collection, such as on immovable property, can have substantial distributional effects. Policy scenarios in which the tax burden is shifted towards immovable property show that the tax shift can yield a moderately positive impact on employment, minimising the distributional effects.

Empirical estimates of India’s transfer system suggests that special transfers do not achieve the objective of providing a more comparable level of public services across states at different income levels. While special purpose transfers are intended to ensure a minimum standard, the analysis finds that there are too many specific purpose transfers, and these are poorly targeted. A reform of the fiscal transfer system is suggested.

In a simulation of the UK’s local finances, not only the mix of funding sources matters for incentives, but the rules around tax and fee policy matter. Even if revenues are initially fully equalised relative to assessed spending needs, significant fiscal disparities can re-emerge in just a few years. Examining the trade-offs between equalisation and incentives inherent in sub-national finance reveals the importance of design choices.

The volume includes both cross-country studies and insights into reforms from individual countries, with several chapters written by experts closely involved in both institutional reform and the day-to-day operation of fiscal relations. The studies show how much the design of policy and institutions matters, even if reforms often happen slowly. The book is a sequel to Institutions of Intergovernmental Fiscal Relations: Challenges Ahead (OECD and KIPF, 2015), broadening and deepening the issues covered there. It also provides insights and experiences from academics and practitioners on key aspects of intergovernmental fiscal relations and how they contribute to inclusive growth. Discussions were fostered by the annual meetings of the OECD Network on Fiscal Relations Across Levels of Government.

References:

OECD and KIPF (2018), Fiscal Decentralisation and Inclusive Growth, OECD Publishing, Paris.