South Africa: it is time to rekindle the economy

By Falilou Fall, Head of South Africa Desk, OECD Economics Department

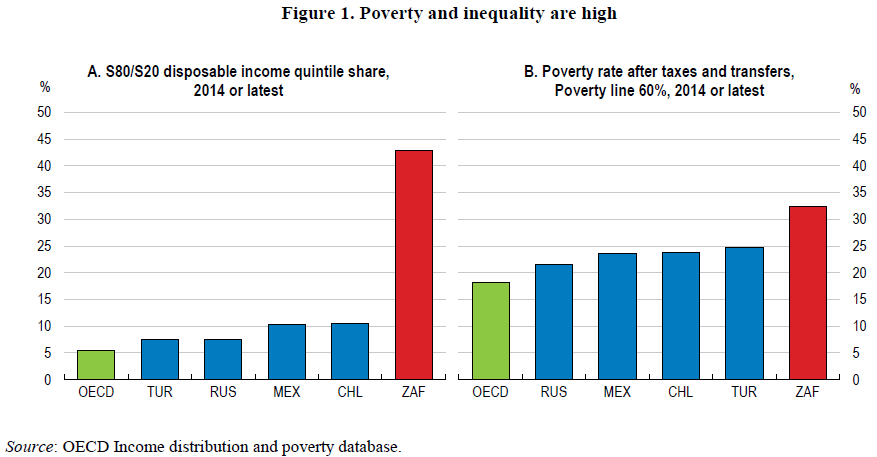

Growth is recovering but inequality remains persistent. Growth is projected to reach 1.5% in 2018 after many years below one percent or negative in per capita terms. Low growth and high unemployment have adversely affected the well-being of South Africans. Since 2010, inequality, measured by the Gini coefficient at 0.62, has almost stagnated withering the social contract in a context of policy mistrust (Figure 1).

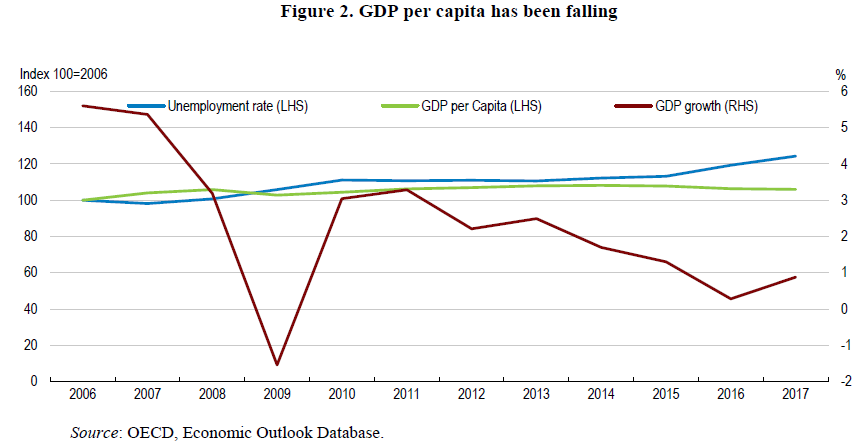

As pointed out by the 2017 OECD Economic Survey of South Africa, the weak growth reflects lacklustre investment and continued low business confidence and the impact of high unemployment, moderate wage increases and persistent indebtedness on sluggish household consumption (Figure 2).

Low growth and weak fiscal discipline contributed to rising public debt burden — from 41% in 2012 to 53% of GDP in 2017. The shortfalls in meeting fiscal objectives, policy uncertainty and corruption concerns in turn led to the downgrading of the government bond ratings to sub-investment level by two major rating agencies in 2017. This makes it harder to meet the large social needs of much of the population.

The election of a new political leadership should brighten the outlook. Business and household confidence are up. Indeed, after three years of contraction, private investment is now expected to drive growth. But, growth perspectives remain too low to create enough jobs and generate enough government revenues for spending and debt reduction, while social and infrastructure needs are high.

In the short run, a more accommodative macroeconomic policy mix can boost growth. Inflation has come down throughout 2017 and, at 4.4% in January 2018, it is in the middle of the Reserve Bank’s target band. Interest rates can now be further reduced to amplify the investment pick up. Smoothing the pace of fiscal consolidation could further sustain demand and thus contribute to growth acceleration. In a low growth era, fiscal consolidation is detrimental to consumption demand, although reassuring for investors (Blanchard et al., 2013; Sutherland et al., 2012). South Africa made limited progress in fiscal consolidation over the last five years as growth kept falling.

Along with slower consolidation, budget reallocation toward more growth-enhancing investment should continue. Limiting wage growth in the public sector and subsidies and transfers to state-owned enterprises would create fiscal space for infrastructure and social investment.

Bold structural reforms are needed to increase potential growth in a longer perspective. OECD South Africa Economic Surveys (2013, 2015) have pointed to many growth boosting reforms: broadening competition in the economy, limiting the size and grip of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) on the economy, and improving the quality of the education system. Important input and technology sectors such as telecommunications, energy, transport and services in general should be opened up to more competition. In particular, telecoms or the airline company, which are in markets with enough competition could be privatised. Moreover, South Africa lacks a proper urban transport system. Putting in place a national plan to expand public transport and allowing more private operators would reduce the cost of transport on the budget and raise well-being.

Job creation remains a major challenge for the quarter of workforce without jobs. The 2017 OECD South Africa Economic survey found that boosting entrepreneurship and growing small businesses can play an important role in creating jobs. Steps have been taken to ease starting a business, but red tape remains a burden. There is room to reduce harmful product market regulations and restrictions to entrepreneurship and entry in professional services. The quality of the education system and lack of work experience contribute to gaps in entrepreneurial skills. Policies should provide more financial and non-financial support for entrepreneurs and small businesses. But, a lack of co-ordination and evaluation hampers effective policy-making.

Greater regional integration within the Southern African Development Community (SADC) could provide new opportunities for growth. Despite large growth potential, economic integration in the sub-region has not advanced much. Intra-regional trade in the Community is only 10% of total compared to about 25% in the ASEAN or 40% in the European Union. Better implementation of SADC protocols and agreements would advance integration and create jobs. Reducing non-tariff barriers by improving customs procedures and simplifying rules of origin would reduce trade costs in the region. Weak infrastructure and institutions and barriers to competition limit industrial development. More ambitious and effective infrastructure and investment policies are necessary at the regional level.

References

Blanchard, O. J., and D. Leigh. “Growth Forecast Errors and Fiscal Multipliers.” The American Economic Review 103, no. 3 (2013): 117-20.

OECD (2013), OECD Economic Surveys: South Africa, OECD Publishing, Paris.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eco_surveys-zaf-2013-en

OECD (2015), OECD Economic Surveys: South Africa, OECD Publishing, Paris. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eco_surveys-zaf-2015-en

OECD (2017), OECD Economic Surveys: South Africa, OECD Publishing, Paris. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eco_surveys-zaf-2017-en

Sutherland, D., P. Hoeller and R. Merola (2012), “Fiscal Consolidation: How Much, How Fast and by What Means?“, OECD Economic Policy Papers, No. 1, OECD Publishing, Paris.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5k9bj10bz60t-en