Global Economic Outlook: Better, but not good enough

By Catherine L. Mann, OECD Chief Economist and Head of Economics Department

Global growth is projected to rise modestly from 3% in 2016 to just over 3½ per cent by 2018 in our latest Economic Outlook. The mood in the global economy has brightened during the past year, with confidence indicators and industrial production increasing, and investment and trade picking up from low levels. Growth is broad-based, including among major commodity producers.

There are now upside risks from investment to improve the quality of capital with more advanced technology, with rapid rises in demand for high-tech products since the second half of 2016. If this is sustained, it would improve cyclical conditions and support a revival of investment-intensive global value chains, boosting domestic demand and productivity.

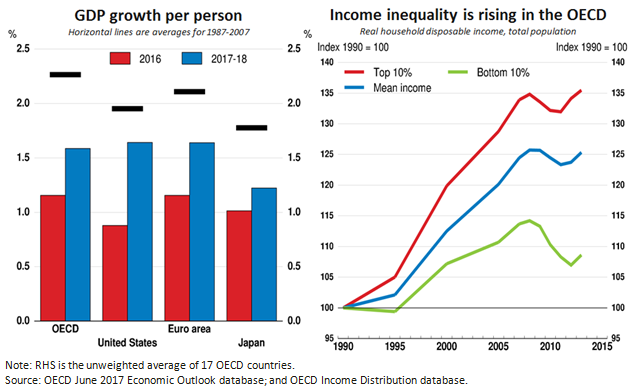

The projected pick-up in growth is welcome as the global economy has been stuck in a low-growth trap, but would still leave global growth below the historical average of 4% for the two decades prior to the crisis. In addition, when viewed in per capita terms, GDP growth for the OECD is even further from past norms and income inequality continues to rise. And while business and consumer confidence have generally picked up, these “soft” indicators have become less reliable in predicting “hard” activity, particularly for emerging economies.

Employment growth has recovered relatively well and headline unemployment rates have decreased in most countries. However, along some dimensions, such as hours worked and part-time working, job quality is more precarious and underemployment remains high. Real wage growth is sluggish and has stagnated for most firms, and is associated with widening productivity gaps to frontier firms, so there are weak foundations for robust consumption growth and widespread improvements in well-being.

Financial stability risks persist and could derail the modest recovery. Policy and political uncertainties are high. Geopolitical shocks and trade protectionism could catalyse snap-backs in asset prices and realise downside risks. High and rising private credit growth for emerging economies, particularly China, is a concern. Rapid increases in house prices in some advanced economies could lead to financial vulnerabilities. Solving non-performing loans in Europe would help to hasten the recovery.

Inflation in advanced economies is generally below central bank targets. After the global interest-rate cycle turned in mid-2016, monetary policy is appropriately moving toward a more neutral stance in the United States, and Europe and Japan are using forward guidance. However, current market expectations imply a rising divergence in short-term interest rates between the major advanced economies in the coming years. This creates risk of sharp exchange rate movements, or other instabilities in financial markets.

In this environment, policy needs to promote inclusive growth and manage financial risks. Countries should implement fiscal policy initiatives that mitigate inequalities and provide long-run benefits, such as boosting education, child care, training and mobility. “High-multiplier” public investments in research and infrastructure would catalyse business activity to strengthen growth. An effective fiscal mix also improves the fiscal position and future output to boost debt sustainability in the longer term.

Each country has its own policy priorities to boost productivity, jobs and inclusiveness as set out in our Going for Growth report. Worryingly, the pace of reform has slowed in recent years and much more can be done to boost competition, skills and innovation. The benefits for inclusive growth can be strengthened through coherent policy packages which maximise synergies if implemented together, such as how active labour market policies do more to raise employment and share gains widely if pursued jointly with greater competition between firms.

The global cyclical upturn is not yet assured: the higher productivity and greater inclusiveness needed to improve well-being for all remain elusive. Policymakers cannot be complacent.

References

OECD Economic Outlook, June 2017.