Enhancing financial stability amid slowing growth in China

By Margit Molnar and Ben Westmore, China Desk, OECD Economics Department

Growth in China has been slowing gradually, but GDP per capita remains on course to almost double between 2010 and 2020. As a result, the Chinese economy will remain the major driver of global growth for the foreseeable future. Patterns across the country vary, however: in some areas slowing investment has brought down growth, while in other, mainly less-developed ones, both investment and GDP are growing at or close to double-digit rates (Figure 1).

Growth in recent years has been fuelled by fast-rising credit and has come at a cost. Financial risks are mounting on the back of an inflating housing bubble, high and rising enterprise debt, expanding non-bank activities and enormous over-capacity in some sectors. Liquidity expanded rapidly over the past couple of years as the reserve requirement ratio was lowered gradually (Figure 2). Mortgage lending soared, fuelling housing prices, in particular in the largest cities. A burst of the housing bubble would hurt the real estate, construction and several manufacturing industries. However, household indebtedness remains moderate and prudential regulations for mortgage loans are stringent, so the financial sector could likely absorb the shock. Consumer finance has also grown rapidly, spurred by the expansion of online peer-to-peer lending platforms. Some of these new lenders are loosely regulated and do little to verify the repayment ability of borrowers. While financial institutions should be encouraged to lend only to people able to service their debt, improvements in household financial literacy are also needed.

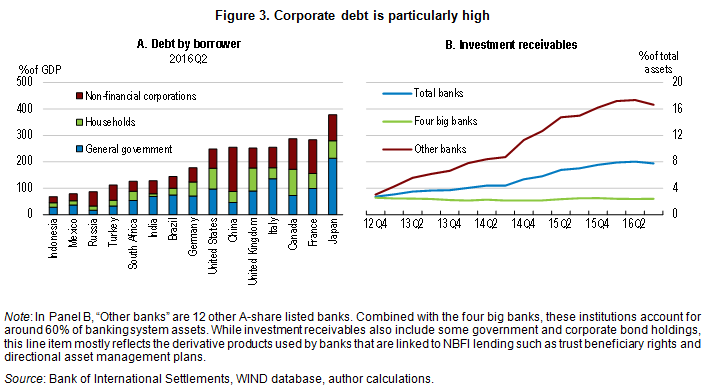

In contrast to moderate household debt, non-financial corporate debt rose from less than 100% of GDP at the end of 2008 to 170% by mid-2016 (Figure 3). This sharp pick-up was due in large part to increased leverage of SOEs. The rapid accumulation of corporate debt combined with a slowdown in economic activity and some of the practices of financial institutions have significantly heightened systemic risks. Under the macroprudential framework announced in January 2016, banks are required to disclose wealth management product exposures on their balance sheet, which will benefit systemic stability. To further contain risks, more effective monitoring and control of leveraged investment in asset markets is required.

The authorities have initiated debt-to-equity swaps in heavily indebted enterprises and approved the issuance of credit default swaps that pay out if there is a default on the underlying loan. A debt-to-equity swap will be initiated for enterprises that cannot service their immediate debts but are considered to be financially sustainable in the medium to long term by the lender. Only a limited group of firms conform to both these conditions, restricting the potential scale of such measures. Indeed few swaps have gone ahead so far as banks have been unwilling to take on the increased risk associated with becoming equity holders. The securitisation of NPLs has also been encouraged, which may be preferable to debt-to-equity swaps insofar as it reduces the exposure of banks to underperforming corporates and the NPLs are acquired by an entity with greater expertise in restructuring the company. Nevertheless, China’s securitisation market is relatively shallow at present, limiting the potential scale of such transactions.

The recently published 2017 OECD Economic Survey recommends enhancing prudential regulation by requiring lenders to take into account borrowers’ repayment ability when extending loans. It also advocates restricting leveraged investment in asset markets.

Reference

OECD (2017), OECD Economic Surveys: China, OECD Publishing, Paris.