Global growth warning: weak trade, financial distortions

By Catherine L. Mann, OECD Chief Economist

The global economy remains in a low-growth trap. In our latest Interim Economic Outlook global GDP growth is set to remain flat around 3% in 2016 and improve modestly to 3.2% in 2017. This is slightly lower than the June Economic Outlook forecast due to weaker conditions in advanced economies, including the effects of Brexit, offset by a gradual improvement in major emerging market commodity producers. More significantly, this string of feeble global growth rates is well-below historical norms.

The prolonged weakness in the world economy generates a self-reinforcing low-growth trap: depressed trade, investment, productivity, and wages in the current weak global environment, in turn lead to an additional downward revision in growth expectations and even more subdued demand. Poor growth outcomes combined with high inequality and stagnant incomes are also further complicating the political environment and increasing challenges facing policymakers.

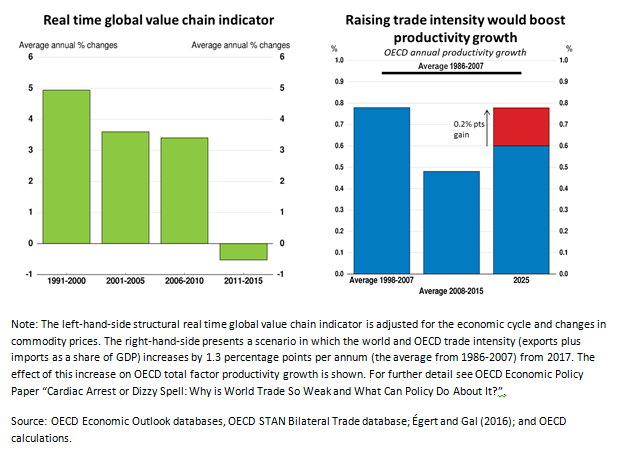

Weak global trade is a particular concern. World trade was growing exceptionally slowly after the financial crisis, and has collapsed in 2015 and 2016. This weak trade growth is both a symptom of and exacerbates the weak global environment. As I have written separately, trade matters for productivity, living standards and inclusive growth. Returning to robust trade growth requires policy action to deepen global integration, but even more importantly to share the benefits, as detailed in our new paper examining the trade slowdown and policies to boost trade.

Significant distortions in financial markets create vulnerabilities, made particularly stark against the poor performance of the real economy. Short- and long-term interest rates have fallen further in recent months to very low and – in many cases – negative levels. Around USD 14 trillion of government bonds, more than 35% of OECD government debt, is currently trading at negative yields, reflecting, among other factors, expectations for persistently low growth and expected monetary policy.

Low and negative interest rates underpin widespread and substantial increases in asset prices, both internationally and across asset classes. Equity prices remain high and have continued to increase in some economies despite weak profit developments and reduced long-term growth expectations. House prices are also rising rapidly in many economies. Credit spreads have tightened this year even as overall credit quality for corporate bonds has declined.

These financial distortions raise risks. In particular, a reassessment in financial markets of the path of interest rates could result in substantial re-pricing of assets and heightened financial volatility. As it is, sustained negative and low interest rates challenge financial institutions’ business models and sustainability, demonstrated by the underperformance of bank shares relative to the overall market. Low interest rates also pose significant challenges for pension funds and asset managers, with implications for savers and retirement incomes.

Monetary policy is overburdened with associated risks. Hence, central bank policymakers need to calibrate both costs and benefits of increasing unconventional support.

On the other hand, fiscal space has been created by the low interest rates. In many advanced economies, interest rates have fallen by more than GDP growth, thereby raising the sustainable debt level. Low interest rates have reduced interest expenses. Hence, fiscal policy should take advantage of this fiscal space by increasing quality investment to boost human capital, physical infrastructure and equality. Canada, China, Japan and the US have recently announced fiscal expansion and the UK has signalled an easing in the budgetary stance. Euro area fiscal policy also should do more to support growth, such as easing the application of the EU Stability and Growth Pact and excluding net investment spending from fiscal rules.

Structural reform momentum needs to be intensified, rather than continue to slow. At the Hangzhou Summit earlier this month, G20 countries were only around half-way to their target of 2% additional G20 GDP by 2018 due to sluggish progress on implementation. Worryingly, despite concerns about weak trade, the share of trade policy commitments fell to 6% from 14% two years ago. Reforms to boost trade are a key lever to boost growth and need to be supported by complementary policies that ensure the gains from globalisation are widely shared among citizens.

The more balanced policy mix, making greater use of fiscal, structural and trade policies, would put the global economy on a stronger and more sustainable and inclusive growth path. Improved expectations of higher future growth from more fully deployed fiscal and structural policies would help to ease the burden on monetary policy and facilitate an eventual normalisation of interest rates.

Bibliography

OECD Interim Economic Outlook, September 2016.

Haugh et al (2016), “Cardiac Arrest or Dizzy Spell: Why is World Trade So Weak and What Can Policy Do About It?” OECD Economic Policy Paper No. 18, September, OECD Publishing, Paris.