Untying the knots strangling Brazil’s competitiveness

by Sónia Araújo

Economist, Brazil Desk, OECD Economics Department

There is strong international evidence that trade liberalisation and increased international integration are key elements of a successful growth strategy. Exposure to international competition, sourcing internationally and learning by exporting accelerates technological upgrading and fosters productivity growth. This column explains how three policy instruments are holding back competitiveness by limiting Brazil’s ability to tap into the global pool of knowledge.

Despite a constitutional amendment in 2003 intended to exempt exports from indirect taxes, Brazilian exporters face tremendous hurdles in claiming back indirect taxes paid on intermediate inputs. Poultry exporters, for instance, estimate that the government owes them around 7% of the value of their exports on account of the several indirect taxes paid on inputs. After attempting to claim these credits for years, companies simply prefer to write off these amounts.

The competitiveness of industrial exports is suffering even more than that of raw and semi-processed goods on two accounts: higher rates are applied to products requiring more transformation and indirect taxes are cumulative. Indirect taxes on inputs embodied in exports put Brazilian producers at a disadvantage vis-à-vis foreign competitors who do not pay such taxes.

Brazilian exporters are also penalised by Brazil’s high import tariffs, which are the highest among the BRICS countries for non-agricultural products (see previous post on Brazil: A tale of two industries or how openness to trade matters, March 22, 2016). Together with local content requirements that expand into an increasing number of sectors (oil, chemicals, motor vehicles, telecoms, health, etc.), they prevent Brazilian companies from sourcing at the lowest cost.

Advocates of trade protection often claim that protection raises the performance of domestic industry over time. Brazil’s own experience in this area is sobering. There is no evidence that high levels of protection have spurred Brazil’s exports, which have remained flat relative to GDP (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Brazil’s share of world trade is low relative to its GDP

Share of exports and imports on world’s total exports and imports, respectively

Source: Secretaria de Comércio Exterior (SECEX) do Ministério do Desenvolvimento, Indústria e Comércio Exterior (MDIC), World Bank Development Indicators.

In fact, the share of manufacturing output in GDP has been declining for a decade and manufacturing productivity is low and stagnant (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Manufacturing productivity is low and stagnant

Labour productivity in thousands of constant 2005 USD per employee

Source: World Bank, ILO, IBGE.

By international comparison, Brazil’s industrial sector is small for a middle income country (Figure 3; OECD, 2015).

Figure 3. Brazil’s industrial sector is small for an upper middle income country

Share of industry in total value added in middle income countries, in per cent, 2012

Source: World Bank.

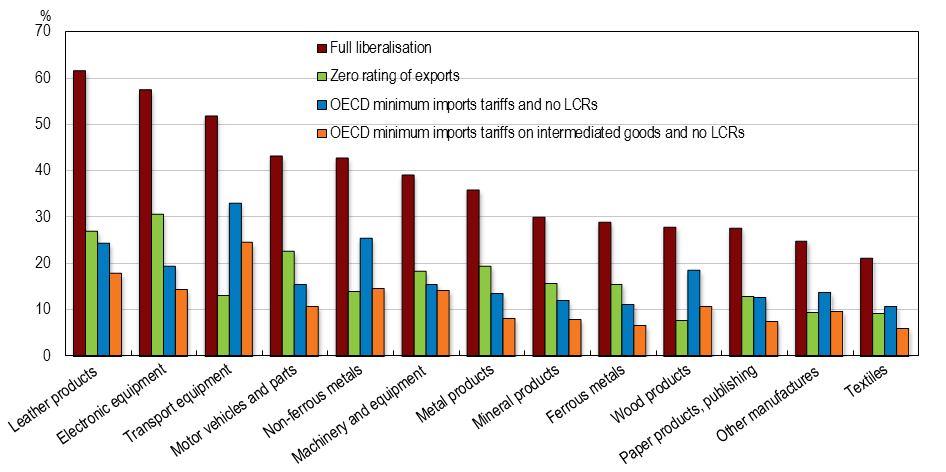

In a recent study we attempt to quantify the effects of lifting these barriers to trade using the OECD Metro model, a computable general equilibrium model of the world economy. The simulation results suggest that reducing import tariffs and local content rules, and effectively exempting intermediate inputs from indirect taxes would boost Brazilian exports, production and jobs substantially. The largest gains would accrue in manufacturing, where exports of leather products, electronic and transport equipment, motor vehicles and non-ferrous metals would all increase by more than 40% (Figure 4). Job creation would be higher in lower skilled occupations, benefiting those at the lower end of the income distribution.

Figure 4. Largest Gains in Exports

Sectors with an increase in exports of at least 20%

The simulation results also suggest that these tax and trade policy reforms would bring clear efficiency gains to the economy: firms would be able to use a higher share of foreign intermediate goods and final goods would in turn be sold at lower prices, enhancing export competitiveness and benefiting Brazilian households.

Another result from our simulations is that it pays to go for a big push. The benefits of a wide-ranging trade liberalisation would far exceed those of partial reforms. Overall, getting rid of these barriers would enable Brazil to develop a stronger manufacturing sector and become much more integrated into the global economy.

Find out more

Araújo, S. and D. Flaig (2016), “Quantifying the Effects of Trade Liberalisation in Brazil: A Computable General Equilibrium Model (CGE) Simulation”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1295, OECD Publishing, Paris.

OECD (2015), OECD Economic Surveys: Brazil, OECD Publishing, Paris