Ireland…trading in the global talent pool.

by David Haugh, Head of the Ireland Desk,

OECD Economics Department

Passing through Dublin airport’s sparkling, spacious Terminal 2, sprinkled with bi-lingual English, Irish signs is a fine experience – it’s a modern, global emporium but with a very Irish flavour as anyone partial to a Guinness in departures can attest to. On arrival before you know it, a phalanx of escalators and travellators have whooshed you to the immigration hall. Standing in the non-EU citizens line gazing across at the streaming mobs of EU passport holders, strangely you can feel almost a little exclusive with your own little gateway to Ireland. The other thing you notice is that a good chunk of the non-EU citizens line are young tertiary students, coming to Ireland to further build their educational achievements. Many others in-line are already experienced professionals. This is migration, a phenomena Ireland has experienced for hundreds of years, 21st century style.

Following the severe banking and fiscal crisis 2008-2011, the Irish economy is again growing at a blistering pace. At 7.8% per annum in 2015 it was the fastest growing economy in the OECD for the second year running. By historical norms rapid growth after a banking-crisis-related recession is unusual. As I argue in the January 2016 OECD Observer, the swift expansion is thanks to Ireland’s huge pool of foreign investment and success in the third great globalisation wave. A key ingredient of this success is Ireland’s capacity to attract and integrate skilled migrants and so far it’s doing quite nicely. It may be a cliché but the Irish people really are loquacious and welcoming. That may be one of the reasons why Google brings staff to Ireland, not just to work in Dublin, but also to train for its offices worldwide.

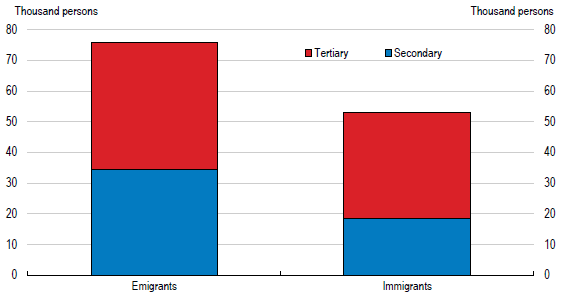

It is true that in the wake of the crisis, mass immigration turned into a mass exodus. The economic recovery has seen this start to turn around but at the trough in 2012 net migration reached -34000 per annum (0.75% of the population). A good chunk of those leaving were prime age workers. The big concern with this is that Ireland is suffering a “brain drain”. However the data presented in the latest OECD Economic Survey of Ireland suggest that rather than “brain drain” Ireland exhibits “brains exchange”, a large proportion of emigrants and immigrants are well qualified. Skilled immigrants complement Ireland’s well-qualified workforce with “hard-to-classroom-learn” capabilities, such as native speaker-level ability in foreign languages. Migrants also allow Ireland to draw on a wider range of education and experiences than a small economy, even with high quality educational institutions, can be expected to provide. Ireland’s large stock of foreign investment is not just there for low corporate tax rates. The ready availability of a global talent mix is an important part of the attractiveness of Ireland to the world’s most innovative multinationals.

More than half of immigrants are tertiary qualified

Educational Attainment, 2014

Source: Central Statistics Office (CSO)

Source: Central Statistics Office (CSO)

Large migration flows can have important implications for trends across the economy and vice versa: large migrant flows can push around housing markets, or fast rising rents and houses prices, as have been occurring recently in Dublin, could discourage them. The system of work permits and qualifications must recognise that to succeed in a global market Irish firms need to be able to draw on a global talent pool. The policy framework should be fine-tuned to deal with these realities and foster an economy and institutions flexible enough to cope with sizeable migration flows.

Ireland is a high-home-ownership country for many reasons but one of them is that rental accommodation has traditionally often been of poor quality. What is required is a more developed rental market and high quality apartments in city centres where many young, educated migrants want to live and work. Government should carry through on plans to densify city centres and height restrictions should be eased from three or four stories as part of this…think the seven stories of Paris…hardly ugly is it?

The government has improved work permit processing but could do more on qualifications recognition. It could also give non-EU student graduates more time to find a job. This is a rich potential talent pool, combining education and skills from Ireland and their own home countries. And training in Ireland is a perfect platform to integrate successfully from. Ireland has invested in these people, why let that handsome return walk out the door?

References:

OECD (2015). OECD Economic Survey of Ireland , OECD Publishing, Paris

O’Connor, B., T. Hynes, D. Haugh and P. Lenain (2015), “Searching for the inclusive growth tax grail”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1270, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Kennedy, S., Y. Jin, D. Haugh and P. Lenain (2015), “Taxes, income and economic mobility in Ireland”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1269, OECD Publishing, Paris.